“The Weather Congress was the supreme body of Earth, able to bend states, nations, continents, and hemispheres to its will. (…) The Weather Congress could freeze the Congo River or dry up the Amazon. It could flood the Sahara or Tierra del Fuego. It could thaw the Tundra, and raise and lower the level of oceans at will.”

– Theodore L. Thomas, author, in the science fiction story “The Weather Man”, 1962.[1]

Mad scientists, space lasers, mysterious satellites… our imagination is often more powerful than technological reality. Dreams of artificial weather control feature prominently in various science fiction stories and films. Such stories often focus on ethical questions. What moral boundaries do we cross if we try to control the weather? What could be the unforeseen consequences of such experiments?

Fact and fiction can also intertwine in public discussions on climate change and geoengineering. As a consequence of global warming, extreme weather events are becoming more common. Messages attributing such extremes to non-existent weather control experiments now regularly go viral on social media. Old conspiracy theories get mixed up with media coverage on the scientific research on geoengineering.

Such fantasies can cloud the facts about climate change and frustrate much-needed climate policies. The emotions behind them often go deeper than scientific discourse alone. For example, many conspiracy theories express a fear of losing control, or a distrust in official institutions.

Science fiction between hope and fear

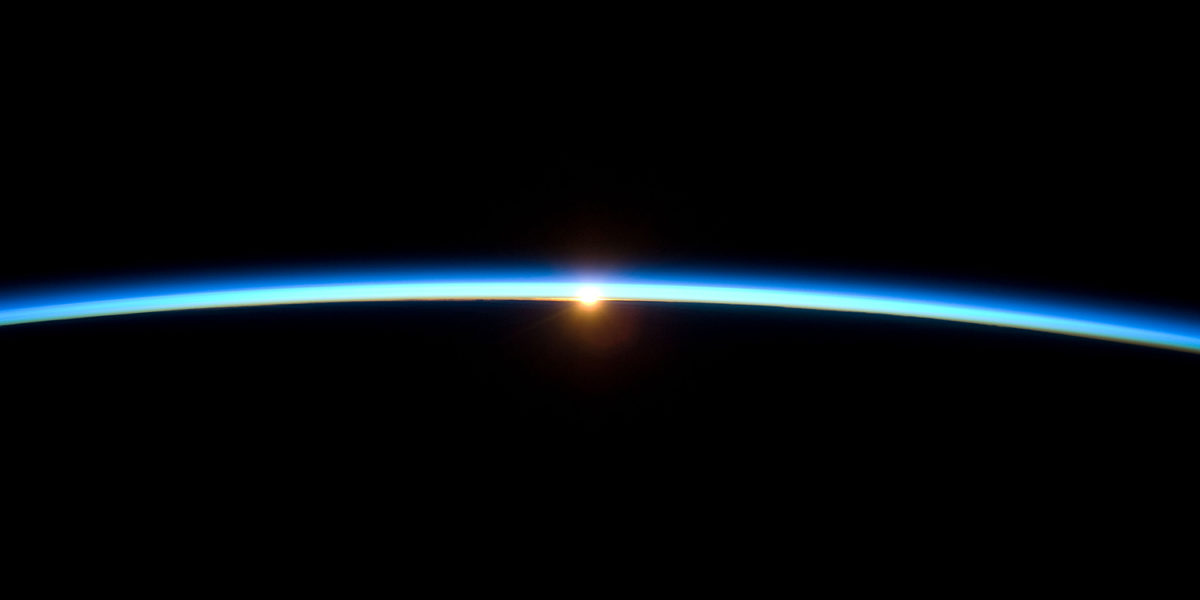

The science fiction genre typically explores our relationship with technology through stories of an imagined future. In some stories, human control over the climate is a hopeful dream. In others, it is a dangerous or doomed project with unpredictable consequences. Science fiction inspires our image of geoengineering, but also reflects the times in which it was created. For example: in early stories of human climate control, written around 1900, humans influence the climate with big cannons or engineering projects. In more recent stories, the weather is influenced from space, often by means of a satellite.

HAARP and chemtrails

In some online spaces, geoengineering and climate change are associated with conspiracy theories that arose in the 1990s. Radiation from the US research institute HAARP is said to secretly influence the weather. The condensation streaks or contrails behind jet planes are supposedly ‘chemtrails’, sprayed by malevolent powers to manipulate the weather with chemicals. These stories illustrate how frightening the idea of weather manipulation can be, but they are not supported by factual evidence. Established in 1993, HAARP explores the outer layer of the atmosphere with powerful radio waves. Such radio waves cannot affect the weather. The white contrails behind jets consist of frozen water vapour from aircraft engines.

Cloud busting

The psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich was a pupil of Sigmund Freud. Reich claimed to have discovered an as of yet unknown life energy, which he called orgone. Alongside other devices, he developed the ‘cloud buster’ in his later US laboratory. Using metal pipes, Reich attempted to get the orgone energy in the atmosphere flowing in order to influence weather patterns. From 1947 onwards, the US government accused Reich of fraudulent scientific claims. Many of his orgone engineering devices were destroyed. Thanks to Kate Bush’s 1985 song Cloudbusting, the cloud buster became part of the public memory. Over time, the popular image of this device became increasingly detached from Reich’s original ideas.

[1] “The Weather Congress was the supreme body of Earth, able to bend states, nations, continents, and hemispheres to its will. What dictator, what country could survive when blanketed under fifty feet of snow and ice? The Weather Congress could freeze the Congo River or dry up the Amazon. It could flood the Sahara or Tierra del Fuego. It could thaw the Tundra, and raise and lower the level of oceans at will.” Theodore L. Thomas, “The Weather Man”, in Analog: Science Fact, Science Fiction, (Brit. ed.; vol. 18, no. 10, 1962), p. 16.