‘Only let the human race recover that right over nature which belongs to it by divine bequest, and let power be given it; the exercise thereof will be governed by sound reason and true religion.’

– Francis Bacon, English philosopher, 1620[1]

People and their environments have been influencing each other for thousands of years. The arrival of Europeans in the Americas in 1492 marked a turning point in world history. Settlers, slavers and traders transformed human societies as well as the world’s ecosystems on an unprecedented scale. Europe was introduced to potatoes, tomatoes and vast quantities of precious metals; America to rats, horses and deadly new diseases.

The Indian writer Amitav Ghosh sees parallels with the science-fiction dream of ‘terraforming’. In terraforming stories, other planets are transformed into a ‘neo-Earth’. According to Ghosh, colonial settlers have likewise attempted to transform conquered continents into ‘neo-Europes’ for centuries.

To this day, specific designs and products are used to ‘tame’ nature and make it profitable. This chapter explores four of those designs. Tools help to exploit natural resources more and more effectively and on an ever-increasing scale. However, this process has unpredictable and unintended consequences for both people and their environment.

Nature as a raw material

Humans depend on their material surroundings for food, tools and shelter. Thousands of years ago, the inhabitants of the Amazon cultivated edible plants, turning the rainforest into a rich “food forest’. In Europe, which saw intense competition between states and investors, increasing emphasis was put on using technology to maximise yields. From around 1450 onwards, the hunt for profitable trade deals and natural resources was a major impetus for distant sea voyages. Maps and descriptions of natural wealth in the newly ‘discovered’ lands illustrated the expected profits.

The Wardian case

At a time of increasingly intensive global trade and colonialism, the overseas transport of plants became ever more important. Traders, collectors, scientists and botanists alike sought out useful and unusual plants from around the world. However, many plants did not survive the long sea voyages. In 1829, British naturalist Nathaniel Ward discovered that plants in an airtight glass greenhouse created their own microclimate. This allowed them to survive for a long time without extra water. With the ‘Wardian case’, the transport of live plants became a much more reliable enterprise. Between about 1850 and 1930, this type of crate contributed to an intensive exchange of plants around the world; such as mango, rubber, and rhododendrons.

The oil drum

Petroleum gained prominence in the global economy from 1910 onwards. It has a high energy density, and unlike coal, it is suitable for internal combustion engines. As a result, oil played a decisive role in the First and especially the Second World War. It became an indispensable source of state power. The growing popularity of the petrol car also contributed to global oil addiction, with petrol promoted as a source of mobility, freedom and self-reliance. In 1928, American marketing guru Bruce Barton declared to oil producers, “My friends, it is the juice of the fountain of eternal youth that you are selling. It is health. It is comfort. It is success.”

The pesticide sprayer

Agriculture is one of humanity’s oldest attempts to control nature. It became radically more expansive and intensive from 1850 onwards, due to innovations such as new types of pesticide. Additionally, in 1909, German chemists developed a technique to make artificial ammonia, enabling large-scale production of artificial fertiliser. In the 1960s, widespread use of such inventions led to a substantial growth in global food yields. But the intensive application of fertilisers and pesticides also causes pollution, strips soil of other nutrients and leads to declining biodiversity. Thus, the biological processes on which our agriculture depends are put at risk.

The refrigerator

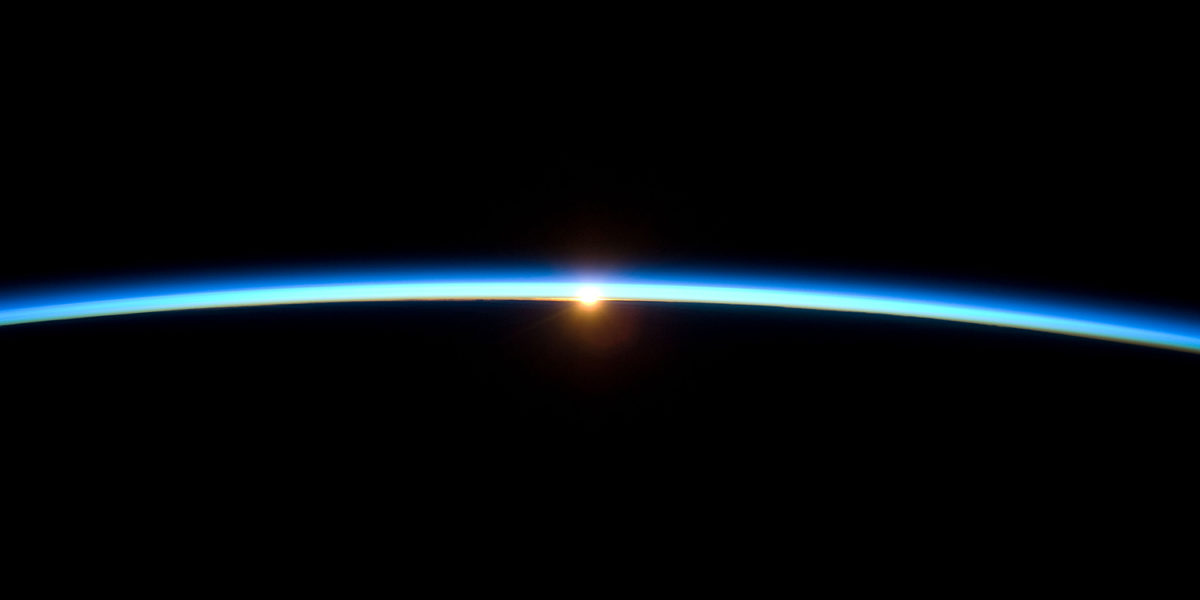

‘We believe that the time is not far distant when people will wonder why their ancestors were so stupid as to live without cooling apparatus in their houses,’ predicted a New York newspaper in 1881. At this time, the first artificial ice machines were already in use among food manufacturers. Early refrigeration systems used toxic refrigerants such as ammonia and sulphur dioxide. In 1928, the safer refrigerant Freon was invented. Cooling systems, such as the refrigerator and air conditioner, conquered the world. But the substances in Freon, so-called CFCs, also proved dangerous. They damaged the protective ozone layer around the earth. An international treaty in 1987 banned the further use of CFCs.

[1] Francis Bacon, The New Organon (1620), in Francis Bacon: The Complete Works (Londen: Centaur Classics, 2015).