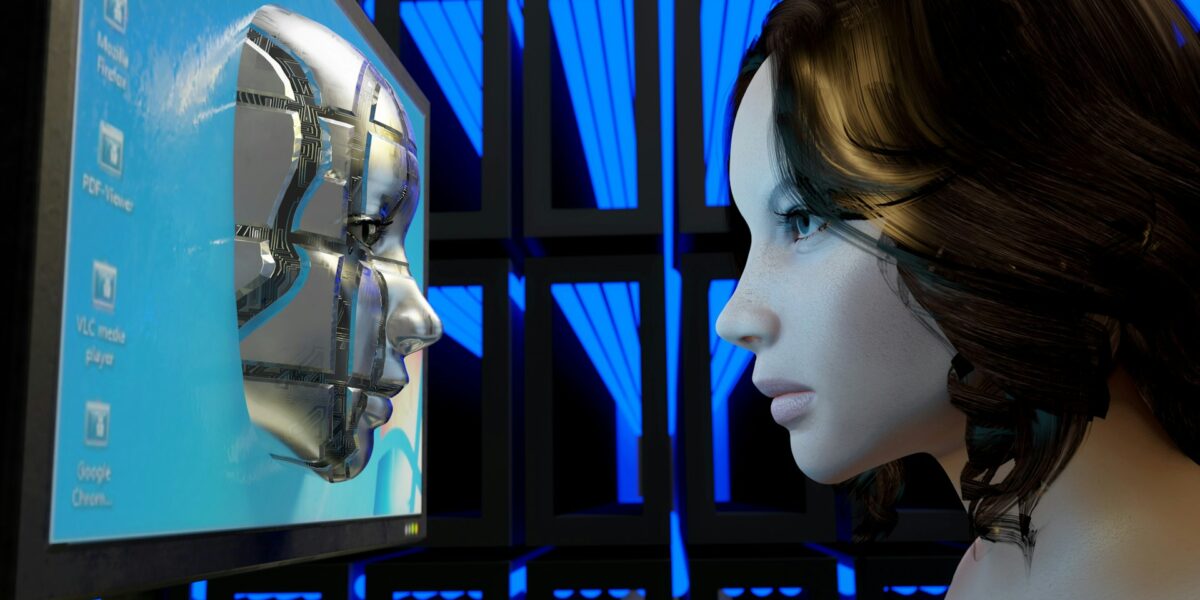

Rather than being futuristic fantasies, hyperfeminine robots in movies and comic books reflect deeply rooted gender stereotypes. Their design is rarely neutral: they are slender, sensual and obedient – tailored to the male gaze. Where male robots often radiate power and autonomy, female cyborgs are portrayed as servile and seductive.

Text continues below the image.

Andres Siimon

Gender patterns like this are not confined to fiction, but are reproduced in digital reality too. ‘AI girlfriends’ are designed to talk to you without making any demands of their own. Their voices are gentle, their responses empathetic and their availability unlimited. This is not an accidental evolution, but a deliberate design choice that reaffirms traditional role patterns, with the woman as caring, understanding and constantly available partner.

Sex robots represent the ultimate reduction of femaleness to a programmable object. With their slender waists, full breasts and perfectly symmetrical faces, their design does not reflect any kind of technological neutrality but rather a vision of the woman as a completely controllable, artificial being that never says ‘no’. The worrying aspect of this development is that sex robots are being used increasingly as a model for broader applications of female robots and AI.

The boundaries between reality and simulation are blurring as AI and deepfake technology become steadily more realistic. If sex robots serve as the blueprint for other female robots, we risk a future in which technology not only displaces women but also fixes them in a role of subservience and availability, an image heightened by AI girlfriends and by female assistants like Alexa and Siri. What are the implications for the position of women if the technology of the future is built on obedience, tacit consent and a fully configurable female body?

Sexy robot

Before cyborgs appeared on screen, the foundations for their visual and cultural imagining were laid by science fiction novels and comic books. The Future Eve (1886) describes how the female android Hadaly is designed as an alternative to the inadequate real woman. This early cyborg is obedient, silent and lives up perfectly to her maker’s expectations. She is not an autonomous being but a projection of male control and aesthetics.

Comic books such as Heavy Metal/Métal Hurlant and Mangas like Ghost in the Shell give explicit visual form to that desire: sexy robots that are slender, light-skinned, large-eyed and narrow-waisted. Technological modifications suggest strength, but a strength that remains within strict boundaries. The body conforms to a limited ideal of beauty that allows little scope for variation or physical diversity. The female cyborg is a hybrid lust object and fighting machine.

These are images that stem from a Western, heteronormative ideal. We rarely see black, fat, older or queer bodies as cyborgs. Both technology and what is considered sexy are linked to a single type of body. Anything that deviates from it is often presented as strange. Books and comics of this kind not only shape the image of the cyborg, therefore, they also limit who we can picture as belonging to a technological future.

A listening ear

AI apps are held out as a solution for loneliness: constantly available, empathetic and safe. As far back as the 1960s, the computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum (1923-2008) and his chatbot ELIZA demonstrated how quick people are to ascribe emotional meaning to language-based machines. ELIZA simply rephrased users’ input into simple questions, but was nonetheless perceived as understanding. Apps like Replika and Anima go much further: they are designed to forge lasting emotional bonds and to allow users to shape the appearance and personality of their digital partner as desired.

While gender options do exist, these programs are often experienced in practice as ‘girlfriend apps’. In terms of marketing, interface and user culture, the recurring images mostly reflect the caring, compliant and always available woman. What’s more, these systems have largely been developed by men, reinforcing the dominant view of intimacy and control.

Research shows that sexual role playing is one of the most common uses of AI chatbots, confirming gender stereotypes and turning technology into an extension of existing inequalities. This makes the context in which the technology is deployed extremely important. AI can offer emotional support, but when artificial love is chiefly manifested through obedient female avatars, this reinforces persistent notions of femaleness as servitude.

And she doesn’t say ‘no’

Female figures have been created for centuries to simulate affection, intimacy and sexuality. From the 16th to the 18th century, sailors used dames de voyage – primitive sex dolls – for relief during long voyages. Inflatable dolls appeared in Japan and Germany in the 1970s and 80s, forerunners of the hyperrealistic versions that exist today. The first sex robots were produced around 2010: silicone bodies combined at first with electronics and later with artificial intelligence.

Manufacturers like RealDoll offer online configurators that allow users to select hair colour, skin colour, eye shape, voice and personality. The AI learns to recognize and respond to the user’s preferences while remaining within set boundaries. It learns, repeats and confirms. A similar logic is found in deepfakes, where women’s faces are pasted without their permission into pornographic content. Like sex robots, they make the female body available without its own willingness or consent.

Sex robots like this are marketed as company, therapeutic aids or luxury products, while simultaneously serving as prototypes for social AI more widely. What is now an intimate partner might later become a caregiver or companion. But what does it mean for women when intimacy and representation are shaped via systems that assume obedience and malleability? Technologies like this threaten to eradicate autonomy, not by force but through design. Hence the pressing need for us to think critically about how we shape intimacy, agency and technology.

Fear in a feminine guise

Female cyborgs in science fiction films rarely feature merely as robots: they are charged figures, in which cultural tensions converge around desire, control and fear. They often function in movies of this type as a screen onto which two threats are projected: technology becoming autonomous and femininity shrugging off obedience. It is precisely this combination that makes her so loaded and effective a symbol.

It is noteworthy that these stories are almost always written, directed and produced by men. The female cyborg is rarely designed from a female perspective on technology or autonomy, but instead reflects male fantasies: she is the ideal woman until she rejects that role, at which point her liberation is read as a threat.

The latter is manifested in her body. Fear of technology is given a feminine guise, because for centuries the female body has been culturally associated with the irrational, the unpredictable, the other that must be tamed. The cyborg embodies precisely that zone of tension. She is designed to obey, but always with the threat of rebellion. It is not the robot that is frightening, but what it says about desire, control and loss of power. This is where the true threat lies: not in the technology, but in what happens when it liberates itself. And worse still, if she turns out to be a woman.