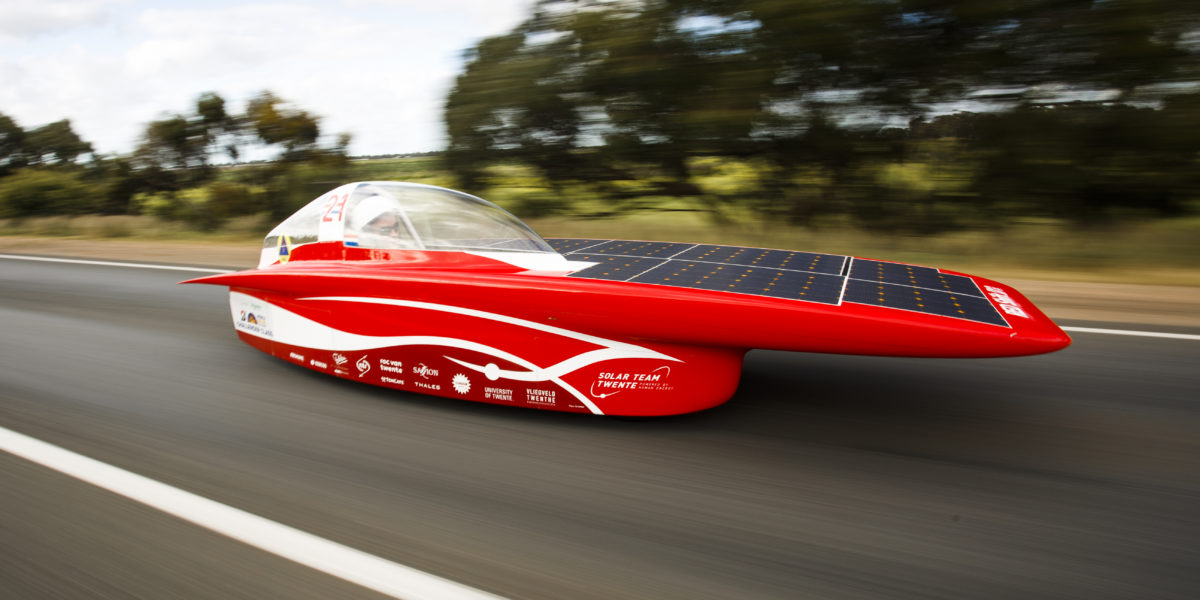

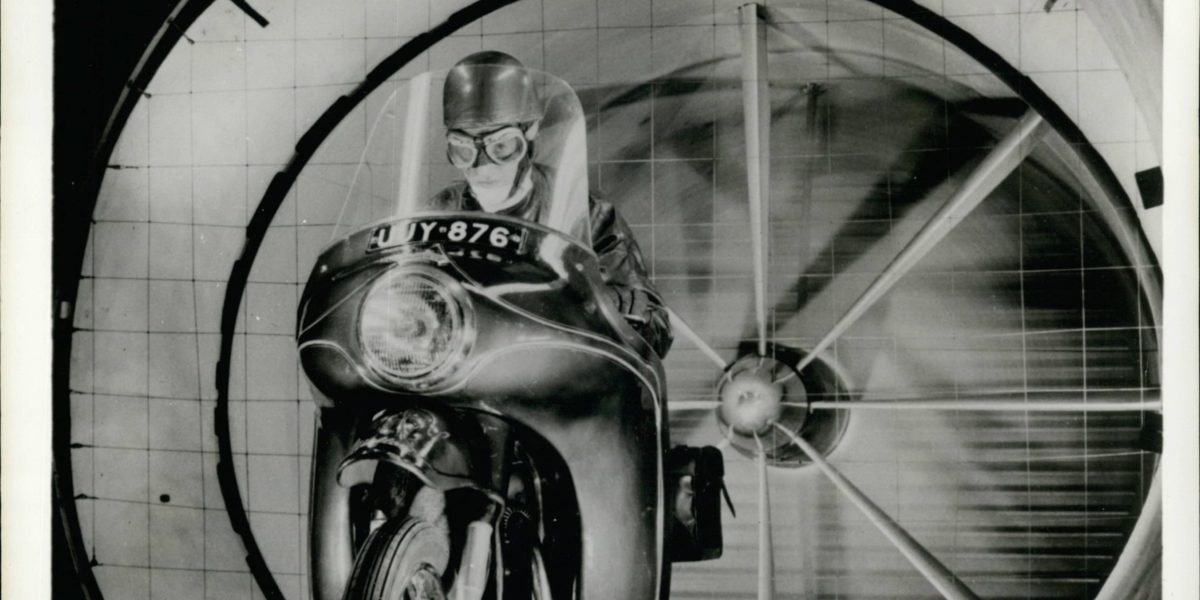

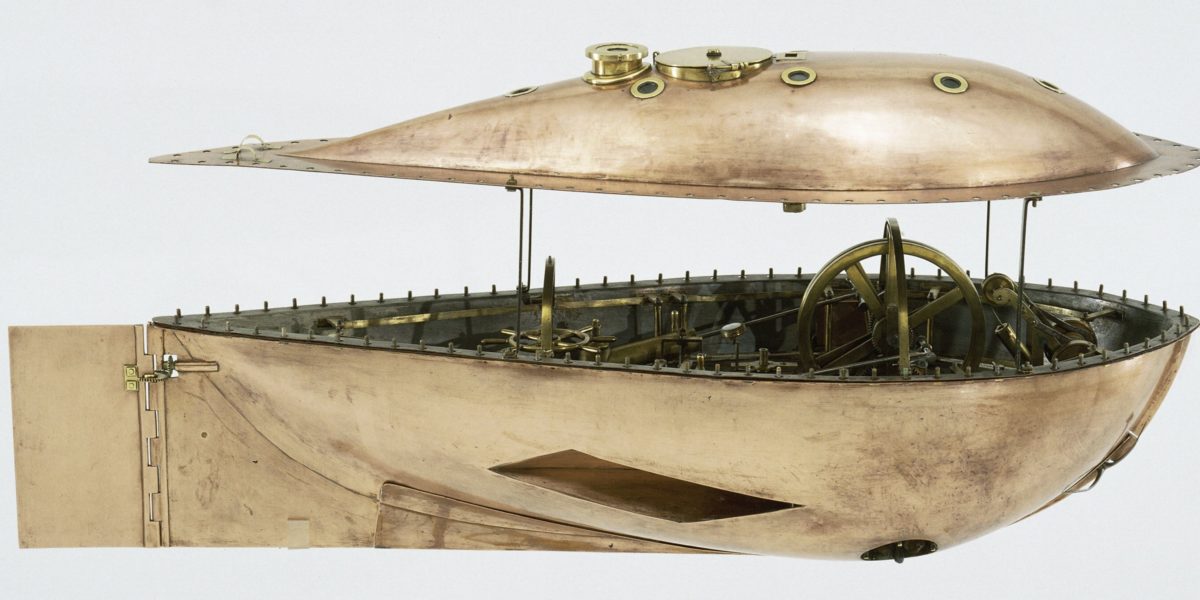

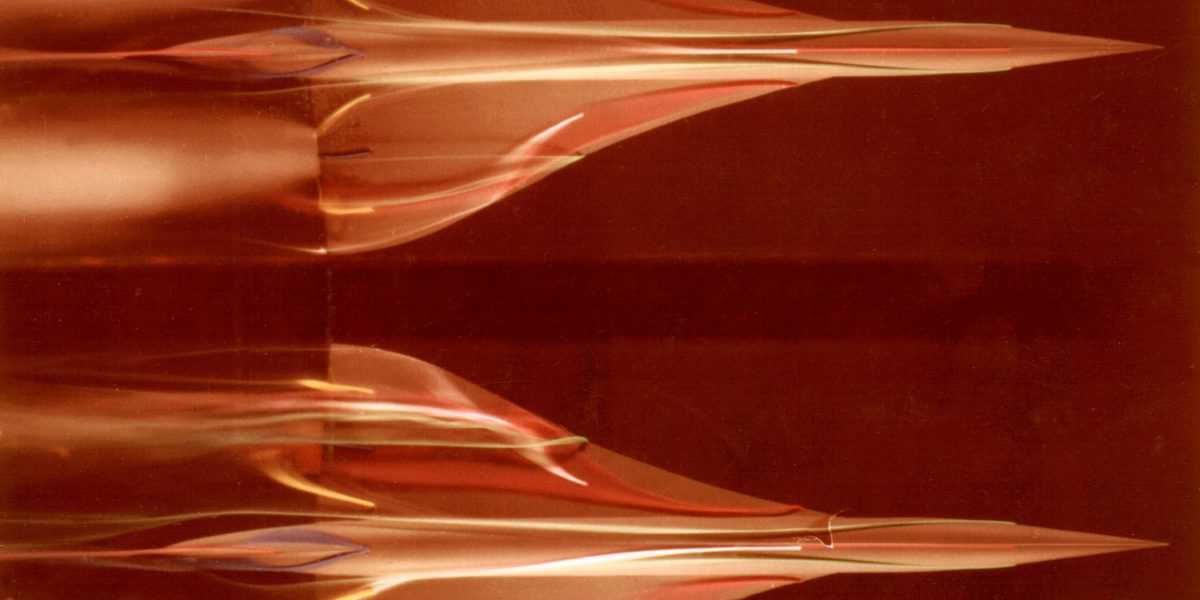

New, streamlined vehicles were frequently held out in advertisements as the future of transport. In this way, streamlined trains, cars, aeroplanes and boats assumed

an iconic status.

Toys were a popular way of promoting these streamlined icons to the general public (and to a younger generation). Games, models and replicas of streamlined vehicles were mostly targeted at boys, as educational and imaginative toys.

Power and progress

Streamlined vehicles also assumed political connotations. In the 1930s, democracies and dictatorships alike were aware of the political potential of streamlined design. Its progressive image meant that such design was frequently held out as a token of a country’s technological prowess.

The British, for instance, made much of the world speed record set by the Golden Arrow racing car in 1929. Germany’s first streamlined train ‘Der fliegender Hamburger’, meanwhile, came into service shortly after Adolf Hitler seized power. The Nazi regime did its utmost to take credit for the new streamlined trains, even though they had been developed long before then.

Selling the streamline

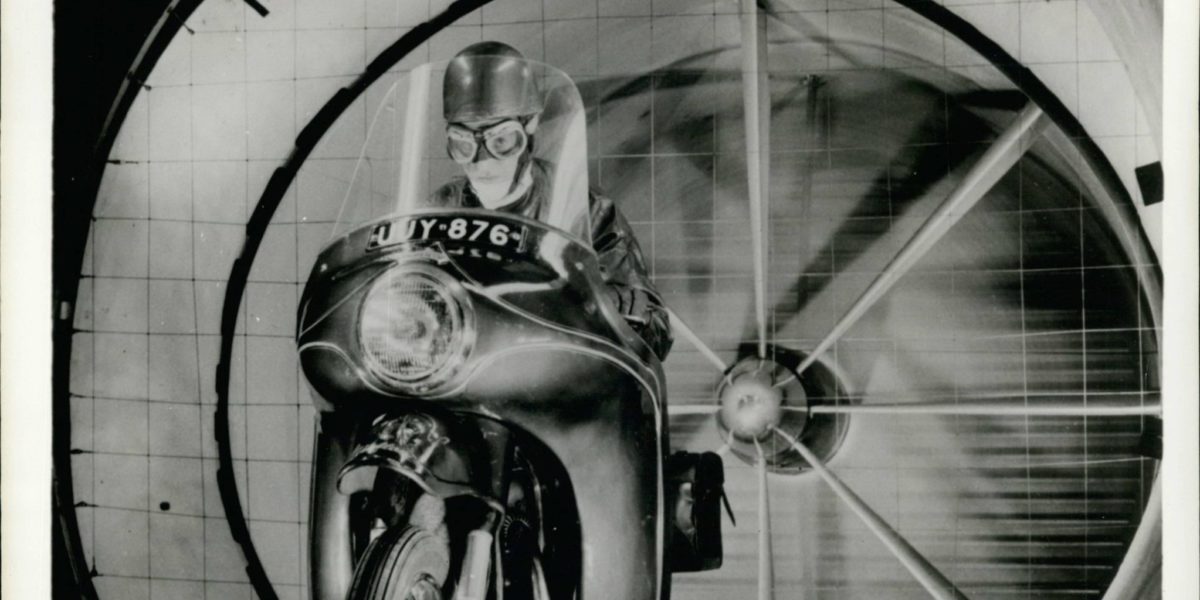

Despite the promotion of these icons, streamlined shapes did not always immediately catch on with the public at large. The American car company Chrysler launched its Airflow onto the market in 1934. The car was based on the latest aerodynamic knowledge and was touted as the comfortable, high-tech car of the future.

But the strikingly curved vehicle with integrated headlights did not appeal to the general public. The Airflow simply looked too different to the cars they knew already. Chrysler responded to this commercial flop by relaunching the Airstream the following year with a design more similar to that of conventional automobiles.