Sneaker culture has become ubiquitous thanks largely to the influence of young people from diverse inner-city neighbourhoods. They have been instrumental in elevating sneakers from pure sportswear to sought-after icons of style.

In the 1970s, sneakers were popularised by a number of youth cultures in different parts of the world. Brands, unaware of this demand, only distributed sneakers specifically to be used for sports. Since supply to non-athletes was limited, without realising it brands were fuelling a thirst for exclusivity.

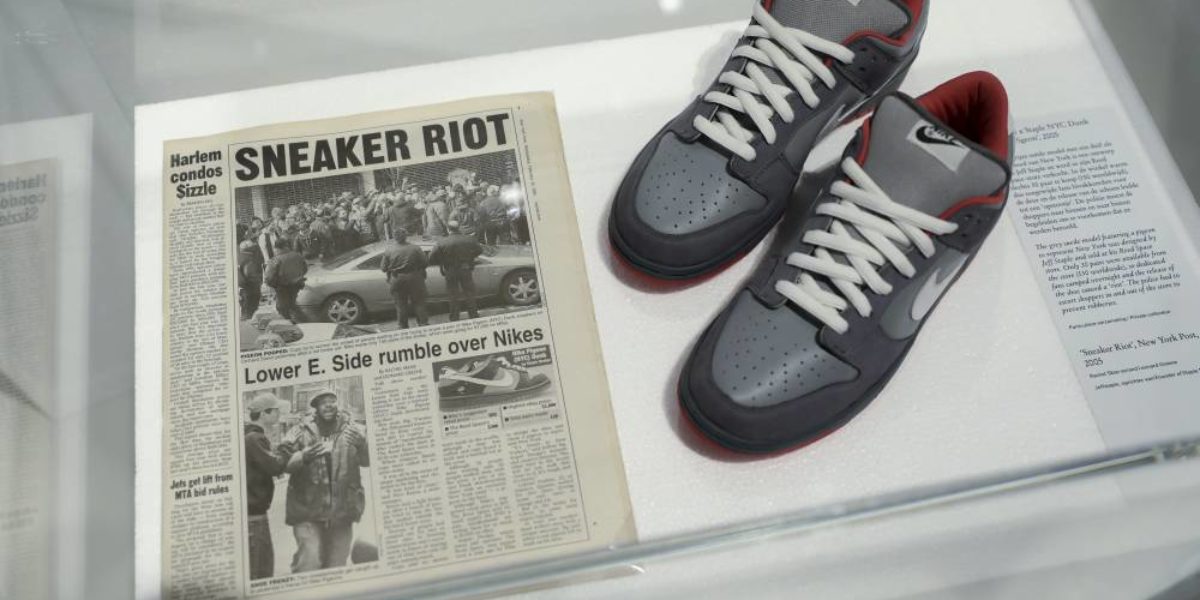

Sneaker brands soon attempted to appeal to young people by introducing endorsements from musicians and sports stars. But it was only when the desire for uniqueness was recognised more widely in the 1990s that a distinct shift in sneaker culture emerged, leading to some of the earliest limited editions and collaborations between sports brands and fashion designers.

Aided by high-profile partnerships and the growing dominance of the internet, sneakers have seen an unprecedented growth in popularity over the last decade. Now, more than ever, they are a platform for experimental design.

Foundations

Young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds are at the centre of sneaker history. Aspirational and striving for social mobility, they use sneakers as a vehicle to express their identity in a way that is at the core of sneaker culture. Whether through emulating sports stars, music heroes or even the local idol, young sneaker enthusiasts are motivated by a desire to fit in and also to differentiate themselves through intricate details. These include matching laces to outfits, customised sneakers, unique colourways and rare models.

Basketbal and Rucker Park

Streetball, which was played at the renowned Rucker Park tournament in 1970s Harlem, New York, influenced basketball and also shaped how spectators dressed. Faster and more physical than professional games, the tournament attracted both local talent and famous NBA players such as Dr J, who pioneered a less restrictive game involving slam dunks and ball tricks. Huge crowds attended, dressed to impress and often wearing the same sneakers as their heroes on the court.

Customizing your kicks

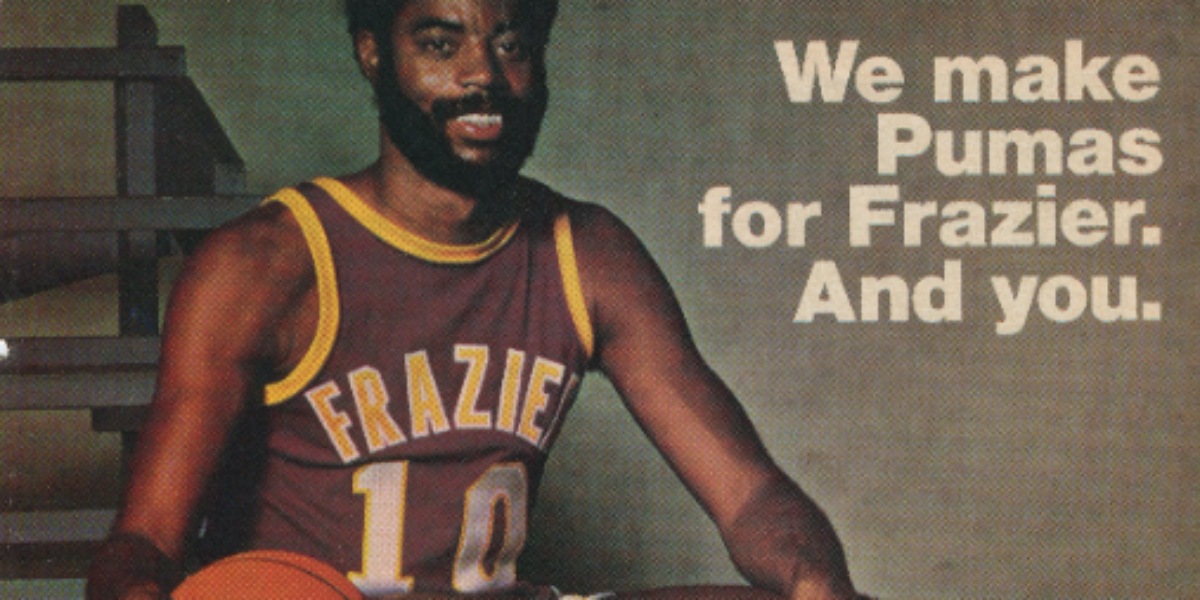

The Puma Clyde – named after basketball player Walt ‘Clyde’ Frazier – was released in various colourways. This provided the opportunity for sneakers to be matched with other elements of an outfit. The type of laces and how they were tied became an important part of the look. Looking after a pair was also important, from brushing the uppers to washing the laces. Reviving sneakers by spraying them a new shade or colouring in the stripes was a way to keep them fresh and prolong their lifespan. With its thick rubber sole and a soft – but resilient – suede upper, the Puma Clyde became the preferred choice of graffiti artists and breakdancers.

Run-DMC and adidas

Hip hop group Run-DMC became the first non-sports stars to secure an endorsement deal with a sportswear brand. Their iconic look, of unlaced Adidas Superstars with the tongue pushed out, encapsulated a long-popular New York style. Adidas shoes were expensive and, because of distribution and manufacturing delays in the 1970s, only available to professional athletes. This initial scarcity made the Superstar one of the most coveted models in 1980s New York. The success of Run-DMC’s 1986 album Raising Hell – and the song ‘My Adidas’ – prompted the Adidas marketing team to sign a million-dollar deal with the group.

Jordan

In 1984, Nike signed a deal with Michael Jordan, at that time a rookie basketball player with the Chicago Bulls. For the first time, the brand created a shoe specifically for one athlete: the Jordan I. The success of this shoe led to further models, eventually evolving into Nike’s only offshoot stand-alone brand in 1997. Clever advertising campaigns by the agency Wieden+Kennedy shaped the way the brand was positioned. For a series of adverts, Jordan was partnered with the film director Spike Lee, in his role as Mars Blackmon, Lee’s Jordan-obsessed alter ego from his 1986 film She’s Gotta Have It. To date, the Jordan brand has released thirty-five sneaker models.

Skating California

A unique attitude towards sneakers emerged from the West Coast of the United States in the 1970s and ’80s, as a result of the growing popularity of skateboarding. Crews such as the Z-Boys sought functional and hardwearing sneakers that suited their vigorous style of skating and could withstand high-speed contact with pavements or concrete. They favoured sneakers from the local brand Vans, because their uniquely responsive business model meant that existing shoes could be adapted to meet the specific demands and needs of their users.

Where Jordan meets skate

Skaters often wore basketball shoes – such as Nike’s Blazer, which offered a combination of robustness and stability. At the time, very few of the major brands created models specifically for skateboarding. Nike’s Air Jordan I became popular with many skaters, especially when the price was discounted after Nike flooded the market. Many models subsequently developed by emerging skate brands in the 1990s bore similarities to Jordan sneakers.

The British football Casuals

Sports shoes were adopted by British football fans in the late 1970s. This culture began in Liverpool and Manchester and came to be known as ‘Casuals’. The uniform Casuals wore was highly coded and differed between northern and southern England, reflecting team rivalries. Rarity was an important factor in gaining status and a sense of belonging, with hard-to-come-by labels such as Adidas from Germany and Diadora from Italy being particularly coveted.

Pin rolls and runners

During the 1990s, London’s Black inner-city youth developed their own approach to styling sneakers. This involved a unique blend of influences from Jamaican dancehall style that paired Click Suits (a matching shirt and baggy trousers) with running sneakers that had highly visible colour accents, such as Nike’s Air Max 1 and Adidas’ Torsion ZX 8000. Oversized trousers were turned up above the ankle, using a method called pin roll, to display the sneaker-and-sock combination.

Grime

Tijdens de millenniumwisseling was het muziekgenre ‘grime’ in opmars in het Verenigd Koninkrijk. Zowel in muzikaal opzicht als qua kleding was het genre een tegenreactie op de uitbundigheid van de ‘jungle’- en ‘garage’-muziekscenes. De look bestond uit een trainingspak met een hoodie en een paar Nike Air Max, ook wel ‘one-tens’ genoemd omdat ze £110 kostten (ca. € 130). De look groeide uit tot een eenkleurig uniform van zwarte trainingspakken met geheel zwarte Nike Air Huaraches, Prada Linea Rossa America’s Cups of de Air Max BW’s, zoals vereeuwigd op de cover van het album Boy in da Corner (2003) van grimeartiest Dizzee Rascal.

Bubble Koppe

Certain sneakers continue to find resonance with youth cultures around the world, who create local identities despite limited access to the latest models. Forgotten and obscure Nike silhouettes with the design feature known as ‘visible air’ or ‘bubbles’ has found a following since the 2010s in the Cape Flats suburb of Cape Town, South Africa. Devotees, now known as Bubble Koppe (‘Bubble Heads’), started a Facebook group that has grown into a scene with regular events and meetups between collectors.

Cholombianos

‘Cholombianos’ refers to a unique youth culture in Monterrey, Mexico, named after a slowed-down version of Colombian cumbia and vallenato music. Teenage fans have developed a distinctive form of sartorial expression. They favour shirts and t-shirts with overt religious iconography, hand-woven necklaces emblazoned with names, and dramatically gelled hairstyles, paired with customised or colour-matched Converse Chuck Taylor All Stars.

The collector’s mind

Sneaker collectors are both gatekeepers and historians of sports shoes and the cultures that surround them. Driven by a desire to own every version of specific models, a Special Make Up (SMU) that no one else they know owns, or an obsession with a specific brand, collectors have long played an important role in the development of the sneaker industry. Rarity and uniqueness are particularly important to collectors, whether this means locating a special pair of deadstock sneakers in the back room of a small-town sports store or negotiating with peers on early internet forums such as NikeTalk or Dead Shoe Scrolls.

The Three Amigos

When Nike’s Air Force 1 was released in 1982, it was only available in stores for a brief period. It became especially popular in Harlem, New York, which is where the shoe’s nickname, ‘Uptowns’, comes from. Its prevalence across the East Coast of the United States was noticed by three Baltimore retailers – dubbed ‘the Three Amigos’ – who convinced Nike to re-release the model. The resulting Color of the Month initiative from 1984 was the first time a discontinued model had been brought out again in response to consumer demand. This was the start of the now common practice of retro releases, regional exclusives and limited editions.

Gabber – ‘Hardcore will never die’

For a long time, people mainly spoke negatively about the Gabber, while in the 90s it was the biggest youth culture in the Netherlands. It was a youth culture that did not occur internationally. Every city in the Netherlands had its own ‘hall’; in Rotterdam – which is considered the birthplace of the Gabber – it was the Energy Hall. Gabber also had its own dance style, called ‘hakken’ or chopping. This involves taking small steps very quickly to the rhythm of the bass drum. In addition to the dance style, the gabber also needs a matching outfit. This usually consisted of a brightly coloured Australian tracksuit – known as Aussie among the gabbers – and a pair of Air Max BWs. The close fit to the foot and comfort were important for the Gabber, as dance parties could easily last 10 hours. In the Netherlands, the Nike Air Max BW was synonymous with gabber.

Bubbling

The Bubbling dance style originated in the 90s in Rotterdam. Initially, Bubbling was especially popular among the Surinamese and Antillean youth in Rotterdam and The Hague. The parties took place at the Imperium disco in Rotterdam and the Voltage disco in The Hague. The fact that the parties took place in different cities also ensured that there were dance battles between different cities. A mix of Jamaican, Caribbean and American music was played. This was then played on speed by DJ Moortje and the audience was whipped up by MC Pester and MC Pret. Bubbling, of course, also included a clothing style, and this was where the key role of the young people lay. The Air Max 93 was worn most often during the dance battles. The Air Max was the most popular, but other trainers were also worn, such as the Adidas Mutombo and Reebok Pump. In addition to the trainers, the outfit consisted of jeans from Chipie or Energie, Carlo Colucci jerseys and tracksuits from Australian, Rucanor or Leopard. In the Bubbling trend and style, there was a certain overlap with Gabbers.

Visible Air

Different manifestations of the Nike Air Max are popularized by various subcultures across the world: from dancehall, Gabber, Grime, Bubbling to Bubble Koppe. A character of these manifestations is the relationship between Youth culture, music and the Nike Air Max. A relationship Nike was not aware of for a long time. In the Netherlands the Air Max 1 is one of the – if not the – most popular sneaker amongst young people and sneakers collectors. The fact that the Air Max 1 was completely unique in its design, because of the exposed air units and the possibility to dance with them for hours straight, made it so popular.