Thijs Gras is a historian and ambulance paramedic. He has published several books on the history of ambulance care, but he also maintains a particular interest in the history of incubators. Exclusively for the Third Floor, he has written this article on the phenomenon of the ‘incubator as attraction’, in conjunction with the exhibition Women as Technology.

A baby in an incubator strikes (almost) everyone as adorable, especially when it is someone else’s child and you’re unaware of the (perhaps) critical medical situation. Nowadays you have to visit a hospital to see incubators. Access to these wards is reserved for parents and immediate family. However, between 1890 and 1914 anyone could admire premature babies in incubators at World’s Fairs or amusement parks. This was meant to be educational and it evoked feelings of tenderness. Moreover, people paid admission to take a look. In doing so, the public contributed to financing the care of prematurely born infants, which had been set up as a philanthropic project. The aim was to save lives, and these ‘incubator pavilions’ did just that, because the mortality rate of babies in these incubators was lower than in maternity wards in hospitals!

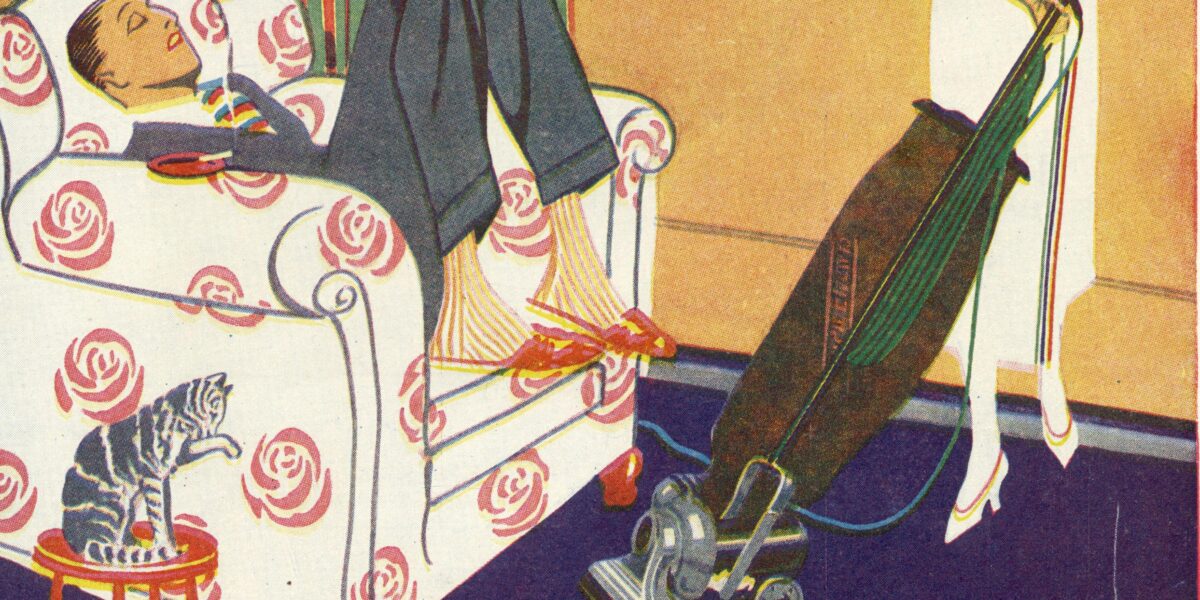

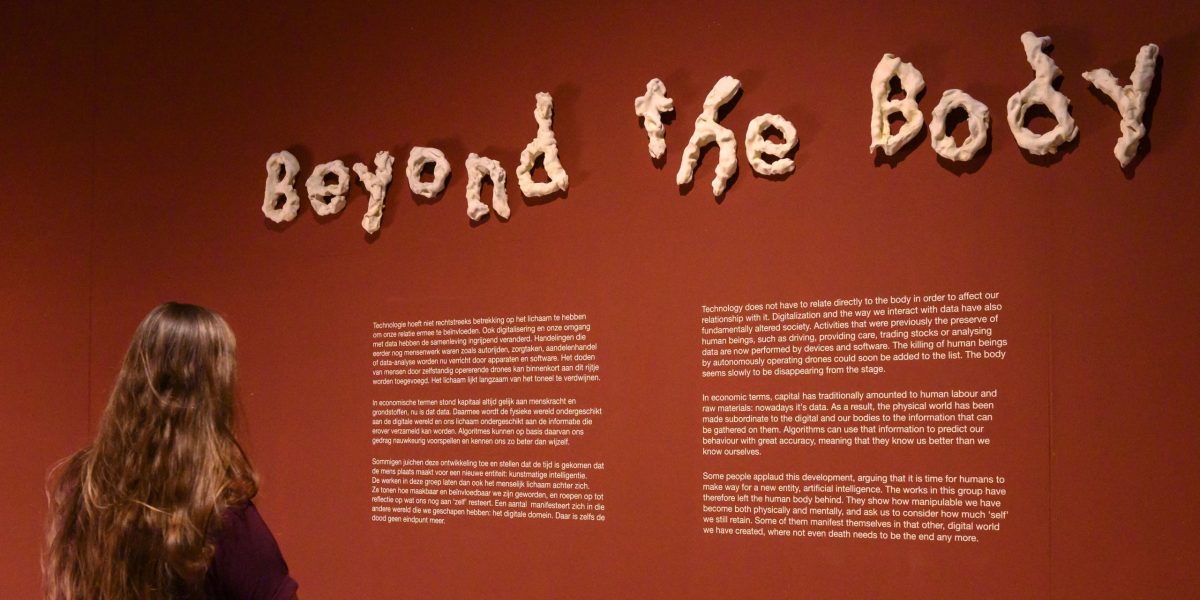

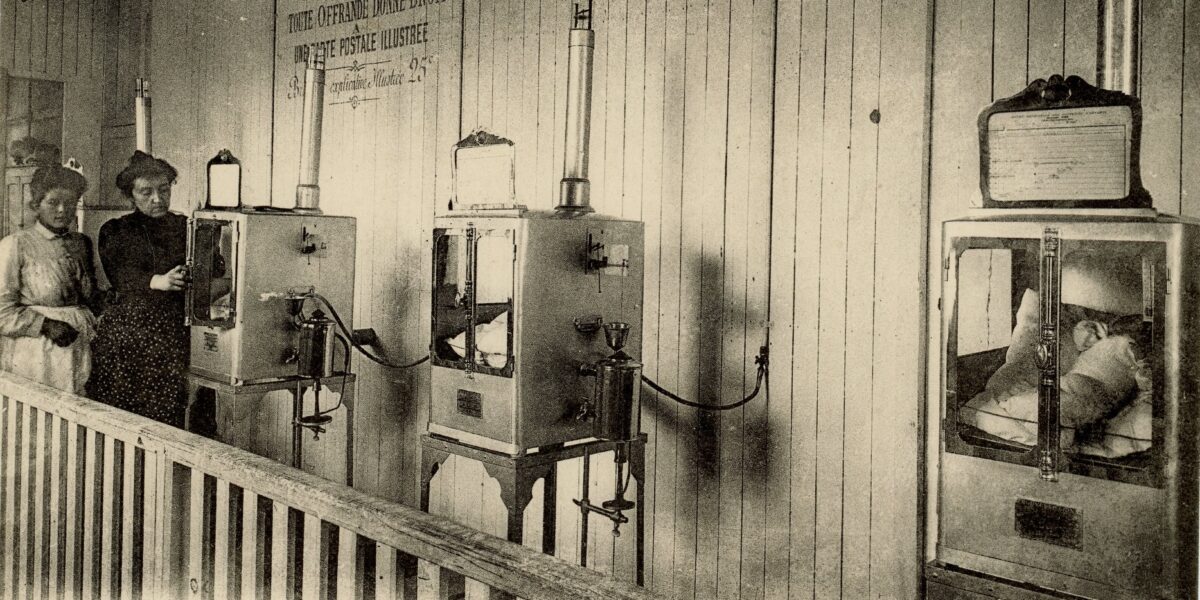

Fig. 1: Interior of the incubator pavilion at the Exposition Internationale, Reims, 1903. Source: postcard from the collection of Thijs Gras.

How did this remarkable phenomenon come about? In 1878, French gynaecologist Étienne Stéphane Tarnier (1828-1897) visited the Parisian Zoo and observed the incubators for (hatching) bird eggs. Recognising their potential application for prematurely born babies—whose most pressing challenge was maintaining body temperature—he adapted the technology for clinical use. By 1880, incubators were being introduced in maternity wards in various hospitals. Especially France was keen to preserve every life, since the country had just lost a deadly war and needed to rebuild its population for future battlefields.

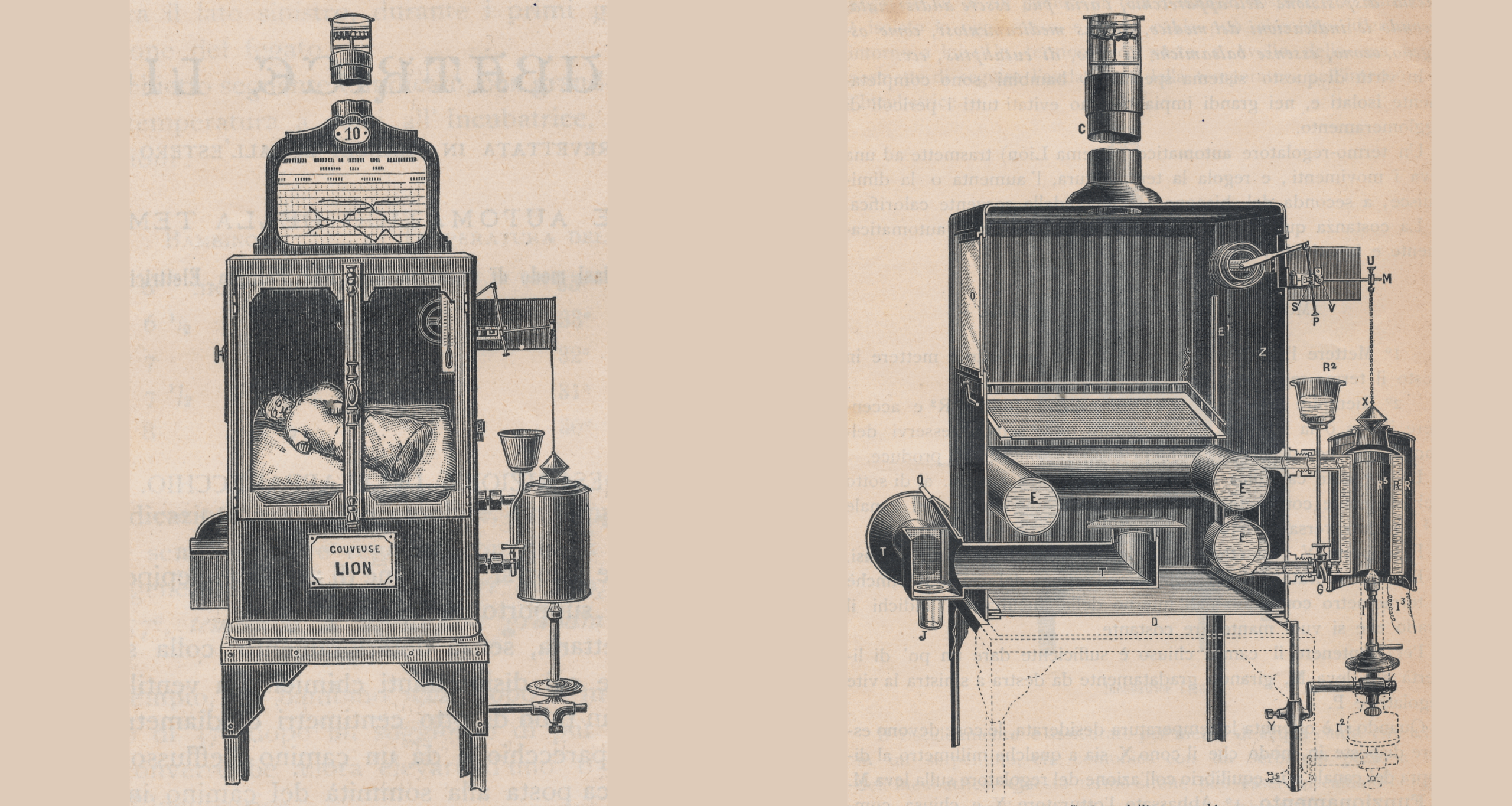

In 1889, engineer Alexandre Lion (1861-1934) developed a large incubator for 5,000 chicken eggs, which he exhibited in Marseille as a tourist attraction. For a modest admission fee, families seeking entertainment could admire freshly hatched chicks. The following year he designed an incubator for human babies and exhibited that too. Poor people were allowed to bring their prematurely born child there, who would then be fed and cared for by a wet nurse–for free. All costs were covered by the admission fees. Lion’s incubator was technically very ingenious and could maintain a constant temperature, thanks to an innovative thermostat and a system of tubes through which warm water flowed. This made Lion’s invention superior to the hot water bottle devices that had been commonly used in hospitals until then.

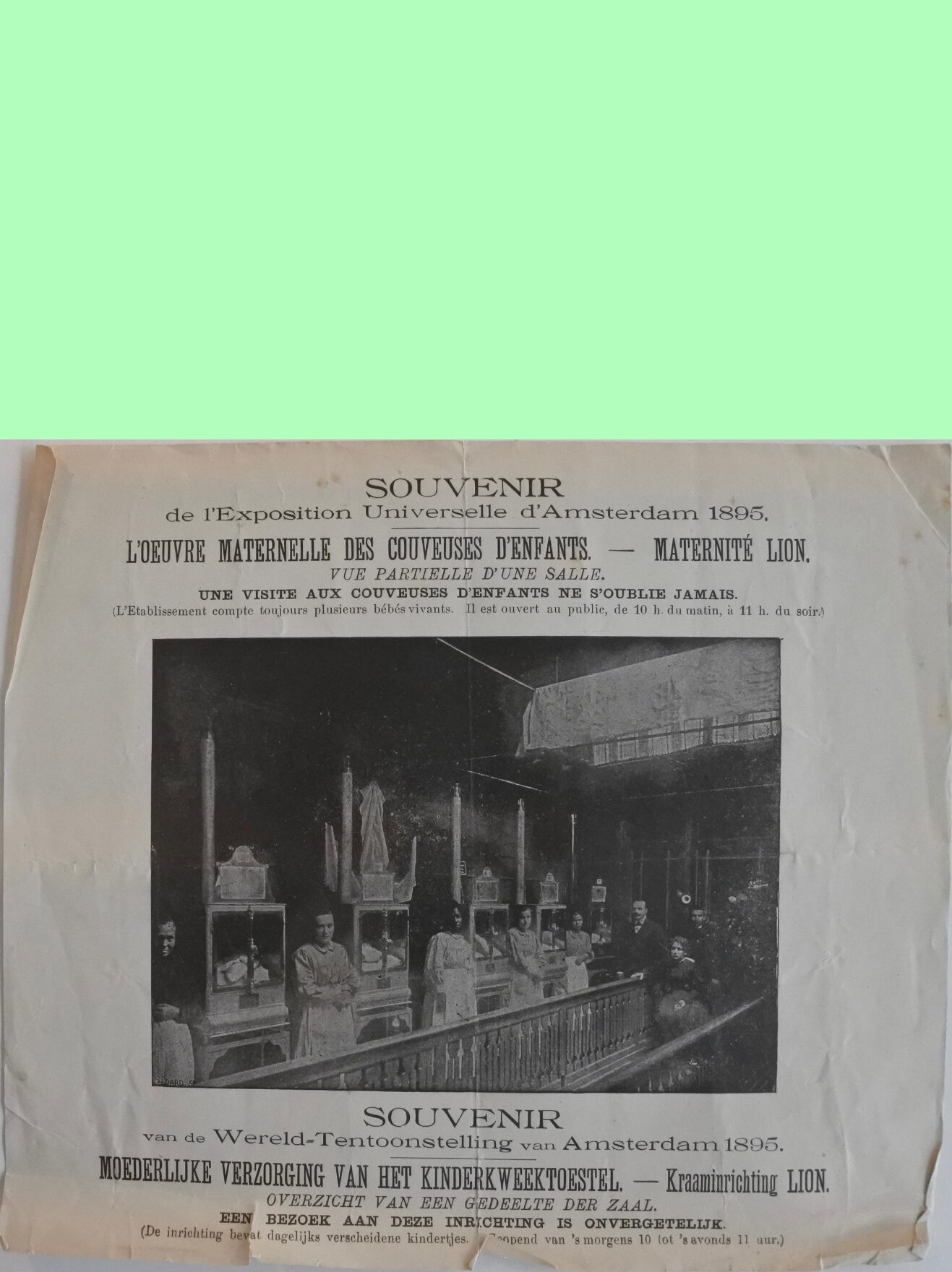

The success of the incubator inspired the establishment of the Oeuvre maternelle des couveuses d’enfants, an organisation that was to encourage the ubiquitous use of incubators, both in hospitals and in home situations, as most births simply took place at home during this time period. Lion established what could be described as ‘incubator salons’ in densely populated neighbourhoods in large cities. To gain even more recognition, he exhibited his incubators, fully in use, at various international exhibitions—beginning in Lyon in 1894.

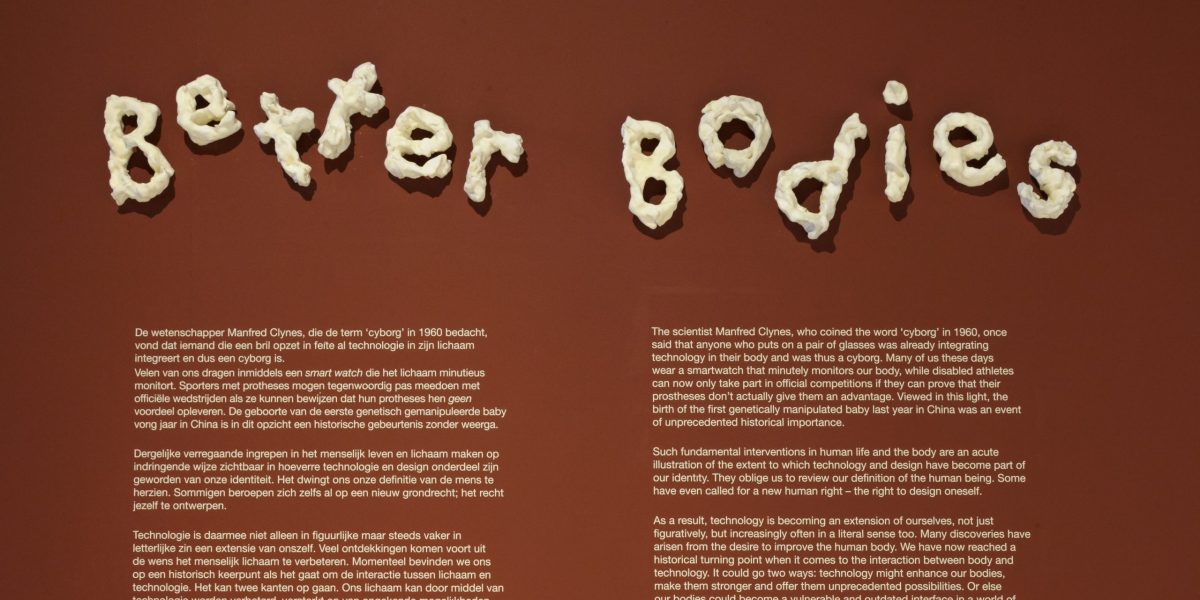

Fig. 3a and 3b: Lion’s incubator was technically advanced and maintained a constant temperature more effectively than the simpler models employed in hospitals. Source: Ricordo dell’Esposizione Generale Italiana, Torino 1898: Oeuvre Maternelle des couveuses d’enfants, Maternité Lion. Turin, 1898 (collection of Thijs Gras).

When Lion heard that a World Exposition was being held in Amsterdam in 1895, he decided to send his incubators to the Dutch capital: it became his first international adventure. A 21-year-old female factory worker (who had given birth to a stillborn child in prison) and an unemployed maid (a mother of newly born twins and residing in the Huis van Ontkoming van de Beth Palet Vereeniging tot Redding van GevallenenHouse of Redemption of the Beth Palet Association for the Rescue of the Fallen× functioned as wet nurses during this World Exhibition in Amsterdam. Lion’s team had ‘obtained’ premature children via the State Midwifery School in Amsterdam, and these babies were placed directly in the incubators. Not all the little ones survived, but with a survival rate of 70%, Lion performed better than contemporary clinical care institutions.

His success inspired imitators in other countries, including—unfortunately—unscrupulous operators who saw an opportunity for easy profit. The most notable was Martin Couney (1870-1950), who adapted Lion’s concept for the American market. Couney established incubator pavilions at amusement parks across the United States. His Coney Island operation in New York became the most famous and longest-running. Over the decades, these pavilions provided care for thousands of premature infants who mostly survived. Couney continued this work until 1943.

Between 1894 and 1914, dozens of exhibitions took place, where people paid to see babies in incubators. These events attracted millions of visitors worldwide. In doing so, these events contributed to normalising the incubator in neonatal care. Portugal provides a striking example: a Portuguese philanthropist visited Lion’s incubator pavilion at the Paris World Exhibition in 1900 and was impressed by the invention.

He ordered four incubators to deploy in the impoverished Alfama district in Lisbon, where infant mortality was extremely high. These incubators, rediscovered and restored, are now on view (without babies) at the Museu do Lactário in Lisbon.

The notion of the incubator as a (public) attraction may appear unsettling to contemporary audiences. Yet, within the context of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was far less unusual. Public curiosity about new technologies was immense—especially when it took over a human function. TV and the internet didn’t exist yet, so if you wanted to see something with your own eyes, people had to visit such an exhibition.

The use of incubators also gave rise to moral debates: should these babies be kept alive? Weren’t you thereby defying the laws of nature? Lion didn’t think so: he was convinced that these babies were to grow healthy, normal children. He also sought to challenge social and racial conventions by employing dark skinned wet nurses to feed white babies (and vice versa!). Some people saw it as undesirable exploitation and were against exhibiting babies. Despite opposition, the demonstrable scientific benefits, educational potential, and capacity to save lives outweighed these concerns. At the same time, the exhibitions undoubtedly appealed to a deeper sense of human curiosity—arguably even to voyeuristic impulses.

Interestingly, the role of the mother was marginalised within this framework of the incubator. Maternal affection and the intimate bond formed during pregnancy were considered secondary to the clinical regimen imposed by the incubator. Mothers (or fathers) brought their premature baby and retrieved them months later, once the infants had reached full term. They had to interfere as little as possible with the care, otherwise the child would be outside the incubator too long or receive too little nutrition. Interfering was harmful to their health. Parental love, in this sense, was postponed until after survival had been secured.

One might ask whether such an exhibition would attract visitors today. I think it might, since a vulnerable baby in a nurturing incubator remains an intriguing image that many people would want to see with their own eyes…