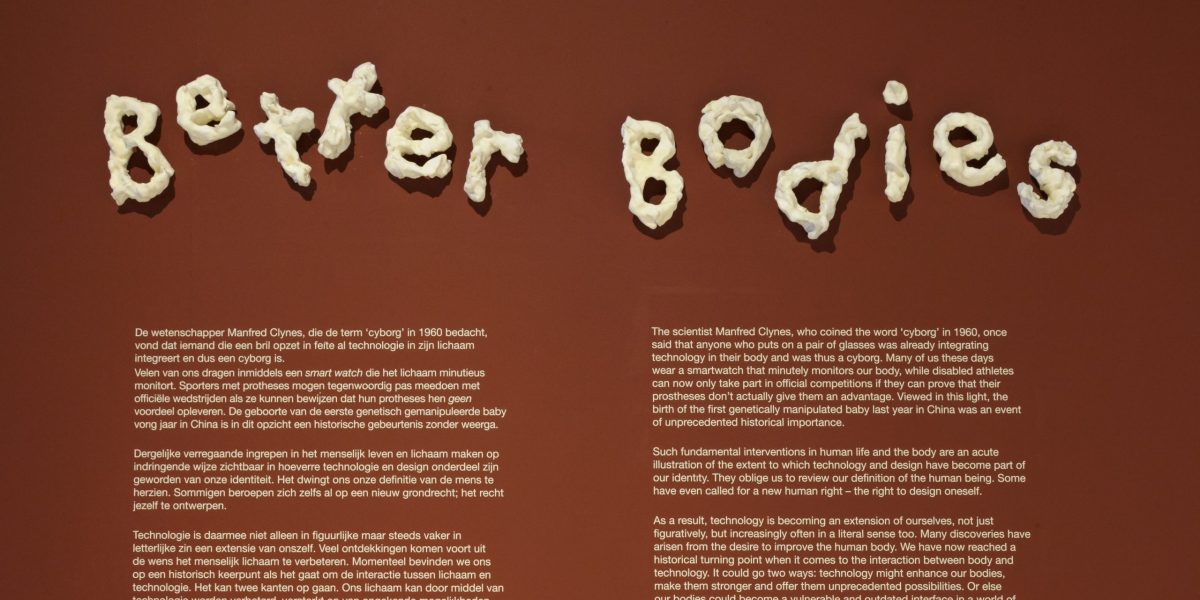

Posthumanism: nowadays we get to decide for ourselves who we will become

Max van der Heijden has a doctorate in the work of Friedrich Nietzsche. He researches themes such as the Anthropocene, eco-philosophy, post/trans-humanism, naturalism and moral psychology. For the Third Floor he wrote the article below.

In an age where our lives are inextricably tied up with new techniques and technologies, it’s important to pause from time to time to reflect on how these things are influencing both us and our society. How are we to deal with modern genetic adaptations that could make human beings immortal? Or implanted chips capable of regulating our aggression? And should we simply accept the use of ‘big data’ that influences human behaviour?

These are the questions addressed by posthumanist artists, writers and philosophers, who reflect on the relationship between technology, human beings and society. In doing so, they focus on one key question: what does it mean to be human? In his essay ‘Artificial by Nature’ (2014), Professor Jos de Mul (Terneuzen, 1956), writes that what makes this question so interesting right now, is that ‘perhaps it will be the destiny of man to be the first species that will create […] its own evolutionary successors’. What this means specifically is that the question of ‘what does it mean to be human?’ is being answered more than ever with the help of modern technologies. Which is exciting.

Humanism

Posthumanism as a movement stems from two earlier philosophical tendencies, namely humanism and antihumanism. The roots of humanism lie in the Italian Renaissance. Humanists argue, as did the ancient Greek philosopher Protagoras (490–420 bce), that ‘humanity is the measure of all things’. They believed that by studying what it is that distinguishes us from other creatures and objects, they could answer the question of ‘what is a human being?’ (or ‘what is man?’, as it would have been put traditionally). Taking their cue from another ancient Greek philosopher, this time Aristotle (384–322 bce), humanists proposed that unlike animals, plants and artefacts (things made by people), the human being is a creature of reason, who can think and can speak.

Antihumanism

All the same, not everyone concurs with the ideas of the humanists: antihumanists, for instance, are extremely critical of humanist thinking. To them, humanism is a ‘border concept’. What they mean by this is actually quite straightforward: when you state what a human being is – a creature of reason who can think and can speak – you are also implicitly saying what a human being isn’t, namely someone who cannot learn a language or cannot think with reason.

According to the antihumanists, humanity has done terrible things in the name of such ‘thinking’. This ‘border concept’ made it possible to distinguish ‘humans’ from ‘non-humans’. The ‘mentally disturbed’, enslaved people, Jews, animals and nature have all been deemed ‘non-human’ at various points in history, with a slew of disastrous consequences. From imperialism and Eurocentric colonialism to the transatlantic slave trade, the Holocaust and the exploitation of the planet to mention just a few.

Posthumanism

Does this mean we ought to abandon the entire humanist project? Certainly not, the posthumanists respond. According to their thinking, we need to reconcile the ideas of the humanists with those of the antihumanists. In other words, we need to rethink what it means to be human: to think critically about human beings, precisely out of love for humanity. Posthumanists view human beings as part of a complex and all-embracing system of humans, animals, plants and technology.

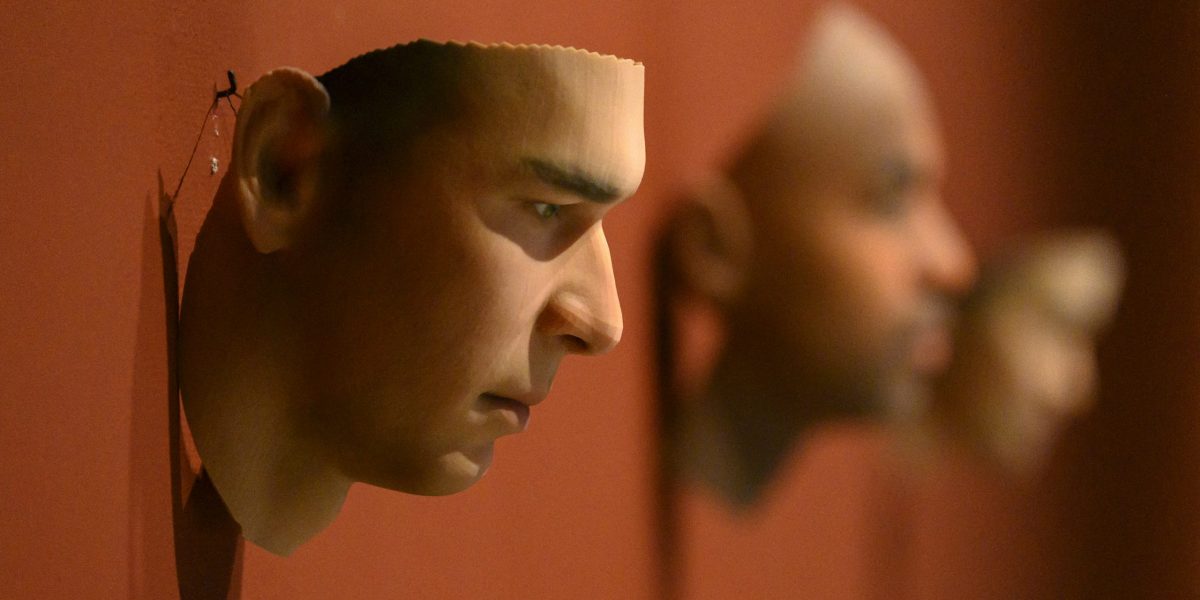

Bart Hess’ Mutants

The work of the artist Bart Hess (Geldrop, 1984) lends itself perfectly to a posthumanist reading. In his film Mutants (2011), he plays with the ‘static’ image of the human being. It shows a human form in a liquid state, apparently suffocating. Hess is suggesting that humans need to escape from this stifling condition in order to be reborn. It also seems as if the human being is constantly changing (metamorphosing) and cannot stand still. But where the form is going, we do not know. Hess challenges the viewer: do you still recognize yourself in this mirror of human beings? Can we define the final stage of humanity, or are we constantly in flux? Should the ‘new human’ look the same as the ‘traditional human’? Or will this ‘liquid human’ create the possibility of other posthuman life forms?

Google Glass

Posthumanists are interested in the relationship between human beings and technology: how is technology changing our world? Does it influence what it is to ‘be human’? Google Glass, a wearable computer in the form of eyeglasses, was launched in 2012. The device was intended to expand and enhance human capabilities and perception of the world via augmented reality. Google Glass displayed information the way a smartphone does, but hands-free. Wearers could operate it using voice commands or a touchpad on the side of the device. The glasses were a major technological advance at the time, but not everyone was positive about the advent of Google Glass. Several critics felt that the glasses violated our privacy, while others argued that they led people to cede their autonomy to the technology. Google Glass never achieved widespread popularity, and with a persistently low level of interest in the product, it was removed from sale in 2015.

We decide for ourselves who we will become

Bart Hess’ Mutants and Google Glass show how different forms of posthumanist thinking are taking shape, whether as criticism, utopia, optimism or question. One thing is clear, though: the traditional boundary between human beings and technology is blurring and that is opening up new possibilities to redefine human identity. The future ahead of us is open and undefined. A precursor of posthumanism, the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), summed up this open view of the future as far back as 1882:

‘We philosophers and “free spirits” feel illuminated by a new dawn; our heart overflows with gratitude, amazement, forebodings, expectation – finally the horizon seems clear again, even if not bright; finally our ships may set out again, set out to face any danger; every daring of the lover of knowledge is allowed again; the sea, our sea, lies open again; maybe there has never been such an “open sea”.’

Nowadays we get to decide for ourselves who we will become.