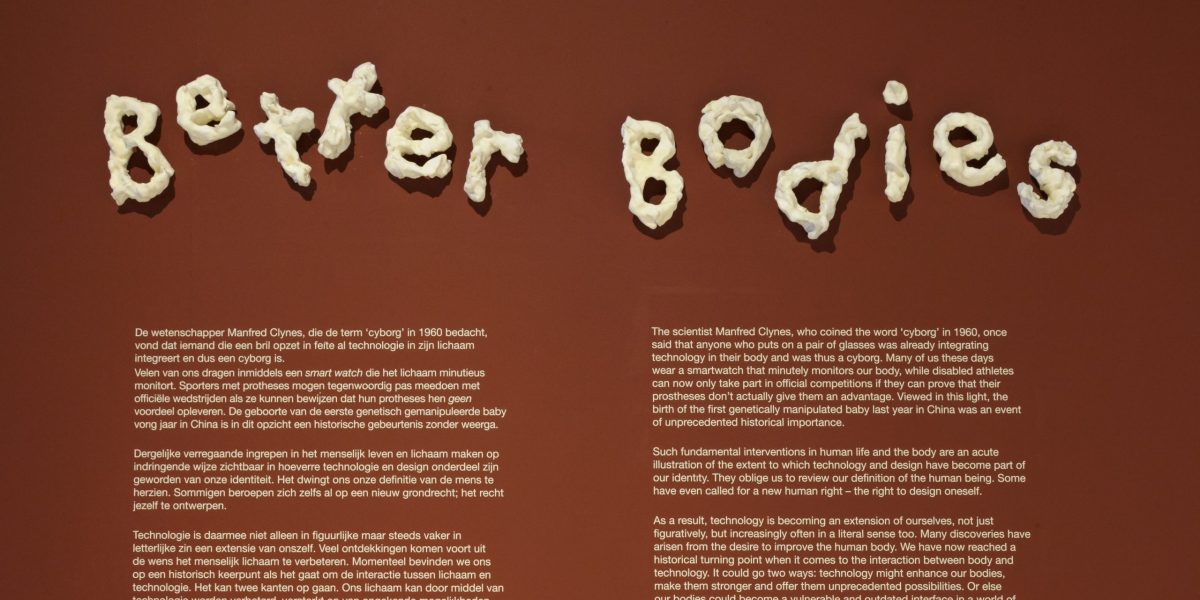

Lua Vollaard is a researcher, curator, and writer. As part of the collective Superkilogirls, she researches the material infrastructure of computers and how it is interwoven with women’s labour. In this capacity, she delved into the archive of the Philips semiconductor factory in Nijmegen. Because her research closely aligns with the subtheme Women as Calculators from the exhibition Women as Technology, she wrote an article for the Third Floor about what she found: how ‘decent girls’ with ‘handicraft skills’ made microchips in Nijmegen—and how their crucial role disappeared from the history books.

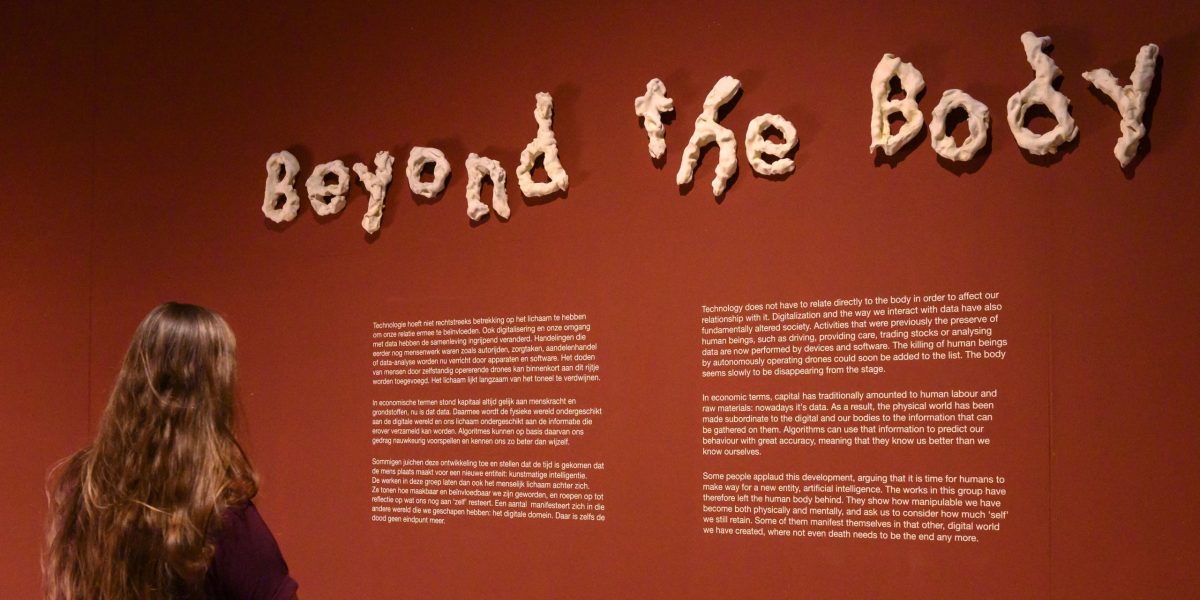

Real Girls’ Work (Echt Meisjeswerk)

The city of Nijmegen is home to a microchip factory. As one of the first places in the world, microchips were manufactured there on a large scale—later, the patent for colour television was even granted to this factory. The workers who assembled these chips were women from Nijmegen, who were hired for their handicraft skills.

Over the course of the 20th century, Philips brought about a revolution in industrial production: the lamp factory in Eindhoven required a constant influx of employees. To expand the factory, Philips first attracted workers from the surrounding area, then from more remote rural regions in the Netherlands, and eventually even from other countries, such as Spain. Eindhoven quickly ran out of ‘fresh blood’ for the assembly line; expansion was on the horizon. The city of Emmen was considered for a new factory, but Nijmegen ultimately won out. The relative proximity, the historic cultural centre, and the luxurious accommodation for directors tipped the scales. In 1953, the Philips semiconductor factory in Nijmegen was opened.

Semiconductors were first developed at the American company Bell Labs in 1947. Technological inventions followed one another in rapid succession; in September 1951, Bell organised a conference to share their findings with 300 scientists from around the world. Philips was the market leader in Europe in the field of electron tubes and anticipated that their market share would be swept away. However, Philips NatLab (Natuurkundig Laboratorium) had been collaborating with Bell Labs since 1950 through a cooperation agreement. Rather than awaiting the competition in Europe to catch up with them, Philips essentially decided to compete with itself in their factory in Nijmegen. Thus began the European race for the microchip.

For fifty years, Philips Semiconductor Factory was based in Nijmegen, where microchips for household appliances were made and a number of internationally important patents were acquired. Colour television was invented here; coffee makers and razors became ‘smart’. After these lucrative years, the factory was eventually taken over by the American giant NXP in 2006. (Note: Recruitment remains a sensitive issue to this day—the factory has had its own recruitment agency from the beginning, and the recruitment agency Randstad is still based in the NXP factory.)

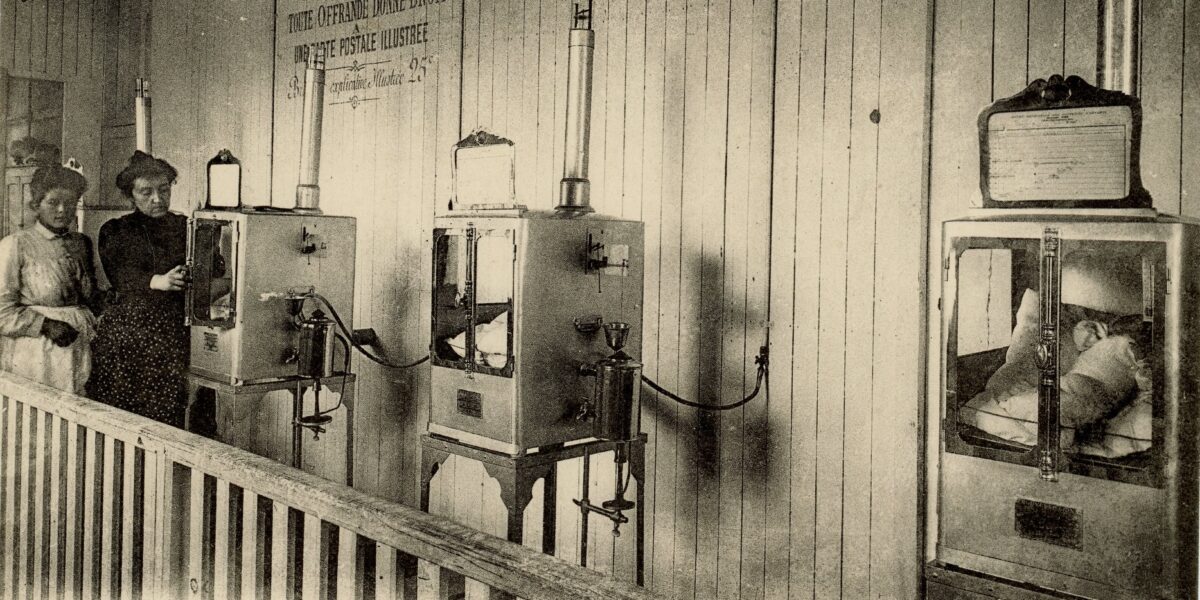

The Philips Semiconductors archive was housed in a shed on the factory site and was moved by a number of former factory employees in collaboration with the LINK foundation to an operational rubber factory elsewhere in Nijmegen. The archive housed there is maintained every Monday by a group of volunteers, mainly retired Philips workers. It comprises two unsorted treasure troves containing chip drawings, silicon wafers in various stages of the production process, and filing cabinets full of printed images. Many photo albums show the working conditions in the factory, groups of women serving coffee, walks along the lake, and women in white laboratory coats leaving the factory. Documentation of office parties is interspersed with images made for recruitment and training purposes. Another scrapbook contains newspaper clippings about the factory.

In the mid-1950s, Philips placed various advertisements in local newspapers and magazines to recruit women. These advertisements show groups of smiling women in white laboratory coats on carefully maintained company grounds. Text printed in italics informs readers about the conditions in the factory, such as the canteen. One of the most prominent advertisements, placed in the provincial newspaper de Gelderlander, advertises “real girls’ work” (“Echt Meisjeswerk”). In almost all advertisements, small print states that they are looking for “decent girls” (“nette meisjes”).

“Real girls’ work” contains a reflection of identity, existing skills, and anxiety about the position of women in the labour market. During the Second World War, women had gone to work en masse; by the 1950s, women were socially permitted to hold a job, on the condition they were unmarried. Philips had a strong interest in emphasising feminine identity in their search for workers: this ‘new workforce’ (i.e. women) was very cheap, but there were anxieties about deploying women in the workplace. The aforementioned scrapbook also includes a letter to the newspaper, complaining that the women who are lured with promises of clean work are being taken away from their household tasks and the care of their children. Local concern about the loss of women to the household drove Philips to a strategy that first and foremost affirms the gender identity of the workers. ‘Decent girls’ is, moreover, a not-so-subtle call to girls with a particular racial and social background. It is difficult to imagine that girls from the Roma camp that ‘made way’ for the factory would have been welcome to work there.

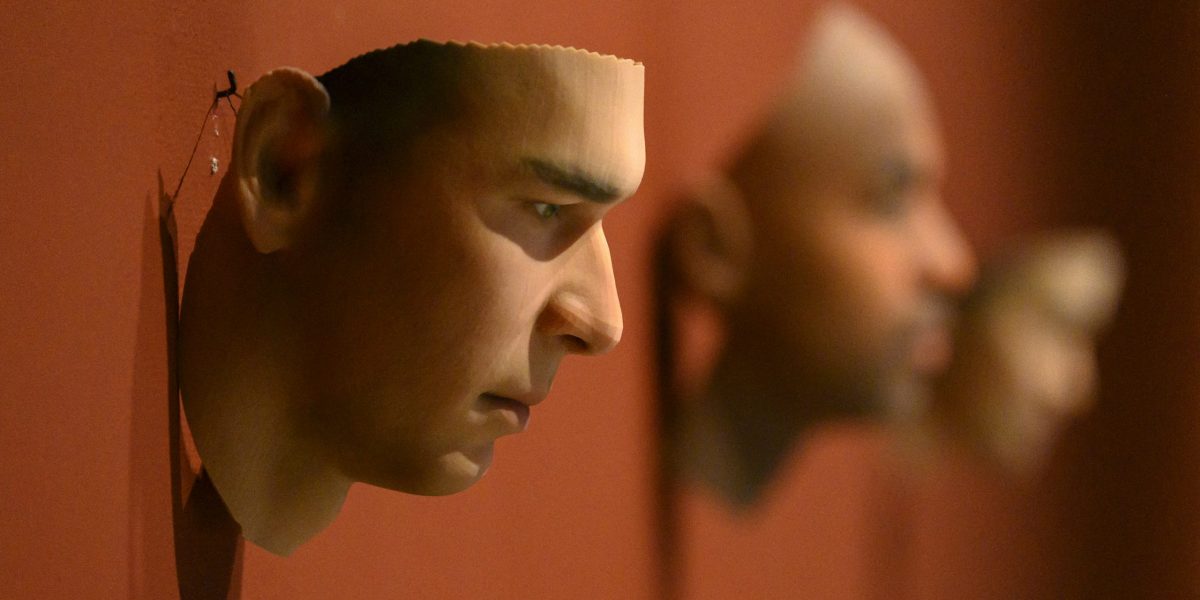

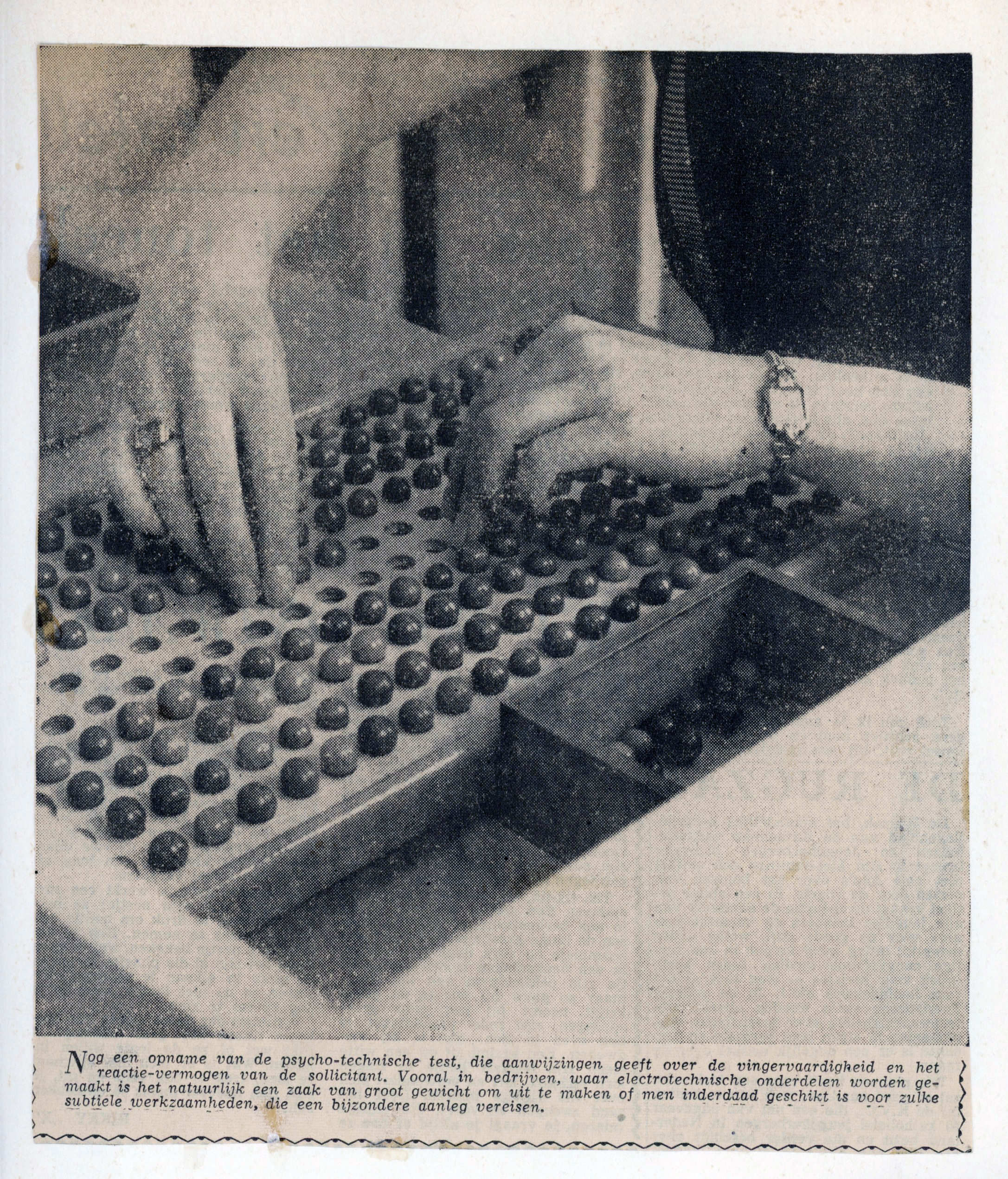

The advertisements showed the workplaces where aspiring female employees could take their seats. They are promoted as clean, bright workspaces, and use the word ‘atelier’ rather than ‘factory’, which evokes associations with heavy industry (Fig. 5). Moreover, it was crucial that the workplaces shown were individual workstations, and thus not part of an assembly line, allowing girls to ‘set their own pace’. One advertisement even shows a ‘psychotechnical test’ administered as part of the application procedure to test dexterity; the hands of a woman, carefully manicured and adorned with metal jewellery, select different coloured balls from a small wooden board (Fig. 6). The suggestion is that the work involved in assembling microchips is much like the (repetitive) handicraft that many women already do at home: knitting, crocheting, and embroidery.

In the article “On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge” (2005), Wendy Chun writes about the programming of the first computers. It was a task performed almost entirely by women whose functions—computers—would later give their name to the machines. The essay follows the development of programming as a professional subfield and argues that women were driven out of the field precisely at the moment when the field began to form: “One could say that programming became programming and software became software when commands shifted from commanding a ‘girl’ to commanding a machine”.Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, "On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge," 33.× Software derives its name from the first computer, the Jacquard loom, which automated weaving. The loom used punch cards to weave intricate patterns by means of levers that held the threads of the loom in place. The machine essentially takes over control of the weaving process from human workers and transfers it to the hardware of the machine, whilst the punch cards determine the ‘software’—the soft goods that the loom produces. At the emergence of programming on mainframe computers, this work was done by as many men as women, because it was not yet a profession. “Women”, Chun writes, “have been largely displaced from programmers to users, whilst they continue to dominate the labour market for hardware production, even as these jobs have moved to the other side of the Pacific Ocean”.Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, "On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge,"49.× Although the introduction of Jacquard machines was fiercely resisted by workers who saw in this shift of control a piece of their body being literally transferred to the machine, a hundred years later in Nijmegen it became, in fact, a temporary form of emancipation. Thanks to their wages, women in the semiconductor industry could perform the same intricate handicraft outside the home that they did at home—but this time, paid.

Afb. 7: Female employee with a silicon wafer full of microchips, Philips Semiconductors Nijmegen, ca. 1980.

The production of semiconductors was a meticulous task before it was automated in the mid-1980s-thanks to the ‘stepper’ machines of ASML. It required a microscope, excellent eyesight, and extraordinary manual dexterity. The actions embedded in our devices contain a history of handicraft. The production of hardware, from the Jacquard loom to the handicraft of Nijmegen’s semiconductor production, has produced a feminine identity that extends beyond the mere emancipation that wages offered. The choreography of semiconductor production, with its repetitive, personalised actions, is anchored in our idea of technological development: what women produce was later established as technological innovation.