Fredric Baas, curator of BodyDrift – Anatomies of the Future, spent two years researching the ‘posthuman’ theme. He shares the fruits of that research in this series of articles. Here is Part 1: ‘What’s it like to be posthuman?’

What does the future of the human body look like?

The future is now! This is 2020, after all. Many of the last century’s science-fiction novels and movies were set in our time, if not in what is already our past. And yet our everyday lives certainly don’t look anything like those spectacular visions of the future. Where’s my flying car, for instance? But one project has been worked on continuously, achieving major advances already and with even bigger ones on the way: ourselves. From smartphones to implants, technology has fundamentally altered our bodies and our relationship with them. Make no mistake: the new human being isn’t some weird vision of the future, it’s you!

Designers and artists these days are asking the same question, each in their own way: ‘What does the future of the human body look like?’ They’re exploring the body’s moral and technological boundaries. Human beings have been improved, protected and made more attractive for centuries. But technological advances mean that this process is now accelerating. The most fundamental development is the increasingly radical impact of technology on our bodies. It’s not only a question of the ongoing merging of human and machine, but also of digitalization and surveillance.

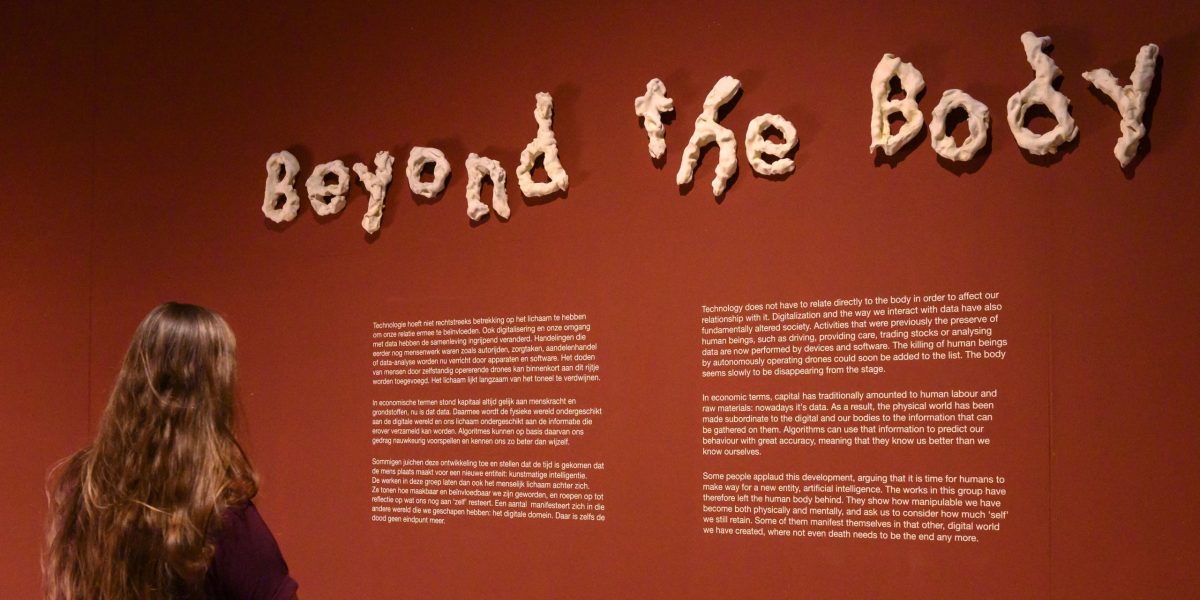

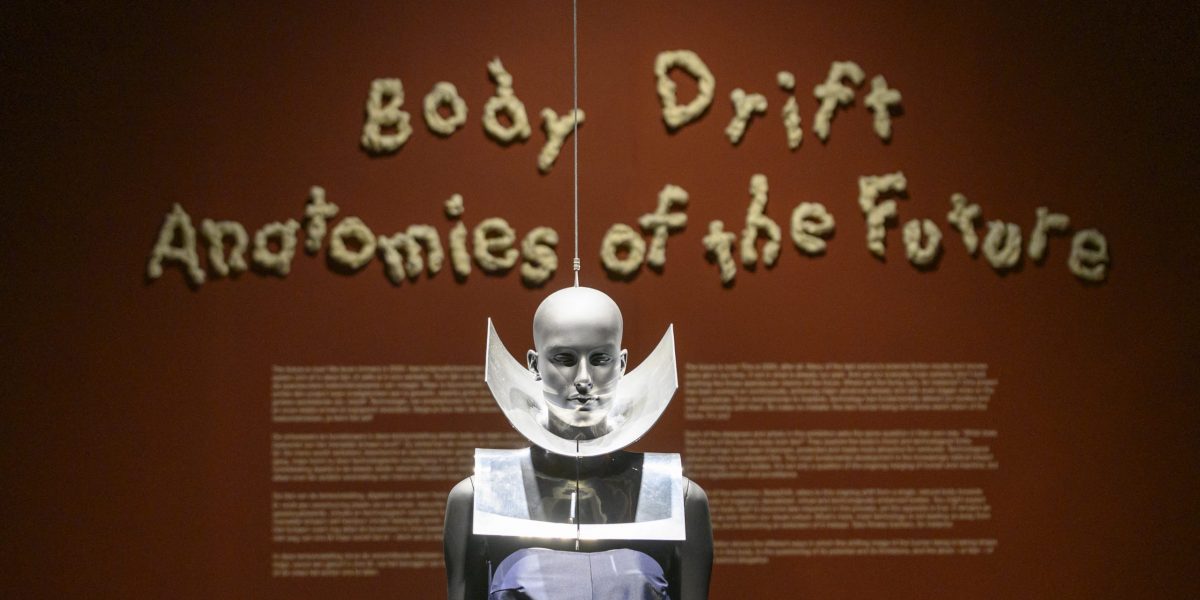

The exhibition BodyDrift – Anatomies of the Future

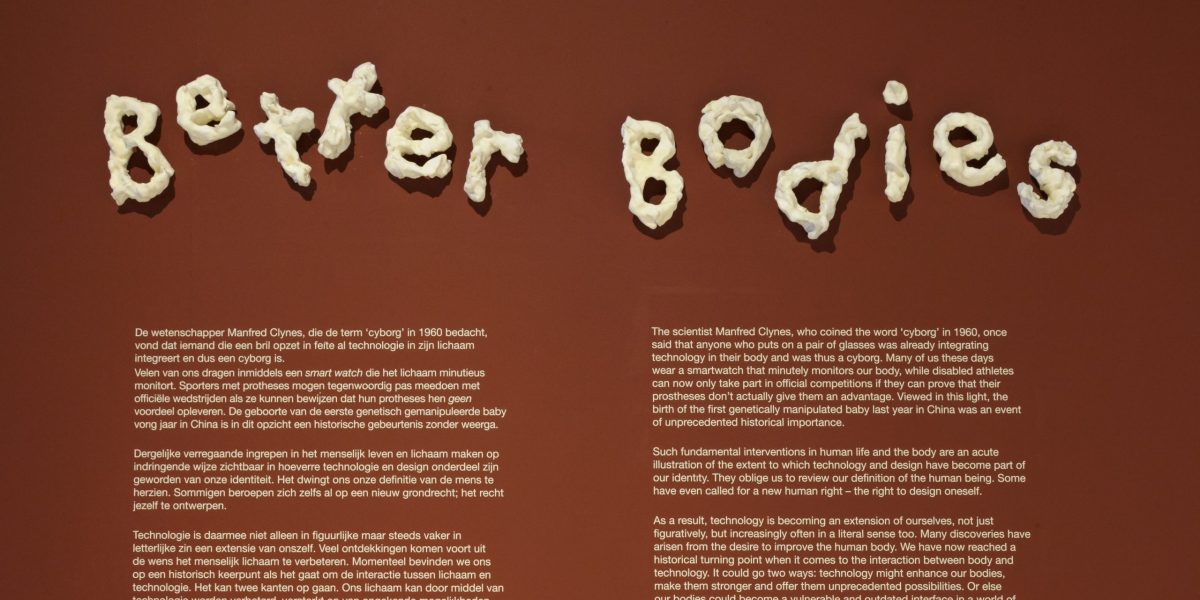

Design Museum Den Bosch was finally able to present the exhibition BodyDrift – Anatomies of the Future to the public from 1 June. The ‘body drift’ referred to in the title also alludes to the developments listed above. A gradual shift is occurring from a single, natural body towards a multitude of imaginary, sexualized, virtual and technologically enhanced bodies. You might expect the human body itself to become less important in this process, yet the opposite is true. It remains as dominant as ever within our visual culture. What’s more, most technology is not leading us away from our bodies, but is actually becoming an extension of it. Take fitness trackers, for instance.

The exhibition shows the different ways in which this shifting image of the human being is taking shape. From faith in the body, to the questioning of its potential and its limitations, and the allure – or fear – of leaving it behind altogether. The focus of the exhibition moves from designs for the body – worn on or even in it – to situations where the body itself is the subject. It concludes by leaving our bodies behind entirely. This article is the first, introductory instalment in a series that addresses the exhibition’s overarching ‘posthuman’ theme, while also reflecting its structure. In both the exhibition and posthumanist thinking, the body functions as an anchor point from which we will drift increasingly further away. First though, what exactly do we mean by ‘posthuman’.

Sorcerer’s apprentice

This is an era of unprecedented possibilities and no fewer downsides. Human beings, like so many sorcerer’s apprentices, have unleashed uncontrollable forces. Driven by neoliberal capitalism, environmental problems, the surveillance society and mutually reinforcing technologies such as genetic manipulation, neural interfaces, artificial intelligence and robotics, the face of life on earth has altered drastically. The traditional, humanist image of mankind too has been fundamentally changed as a result. The question is not so much whether human life can avoid this transformation as when and how it will occur.

From postmodern to posthuman

These developments, which are actually accelerating, have led scholars to label our current period – following that of the postmodern – as ‘posthuman’. The term refers to a paradigm shift unprecedented in human history: the possibility of a world in which human beings are no longer central. It entails the definitive dismantling of dualistic and hierarchical Enlightenment thinking, in which the ‘human being’ was not only adopted as the measure of all other living creatures, but was also implicitly equated with the white, Western male. Consequently, ‘posthuman’ does not so much mean ‘after humanity’ as after the notion of ‘man’ as an uncontested concept.

Everyone a cyborg

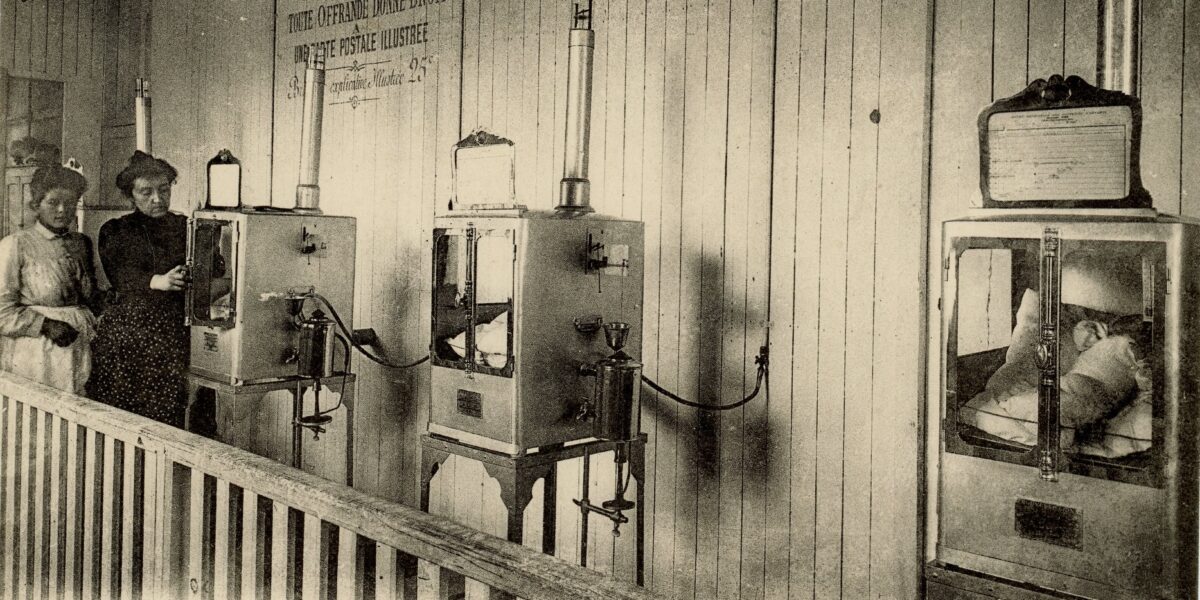

The birth of the first genetically engineered babies in China at the beginning of last year and the fact that there are already several thousand people amongst us who have taken the first steps towards becoming cyborgs oblige us to revise our definition of the human being. Those who utilize biotech and other scientific advances to intervene in human life and their own bodies provide clear visual evidence of just how far that technology – and hence also design – has become part of all our identities. The cyborg pioneer Neil Harbisson states that he and people like him are demanding a new human right – the right to design yourself.

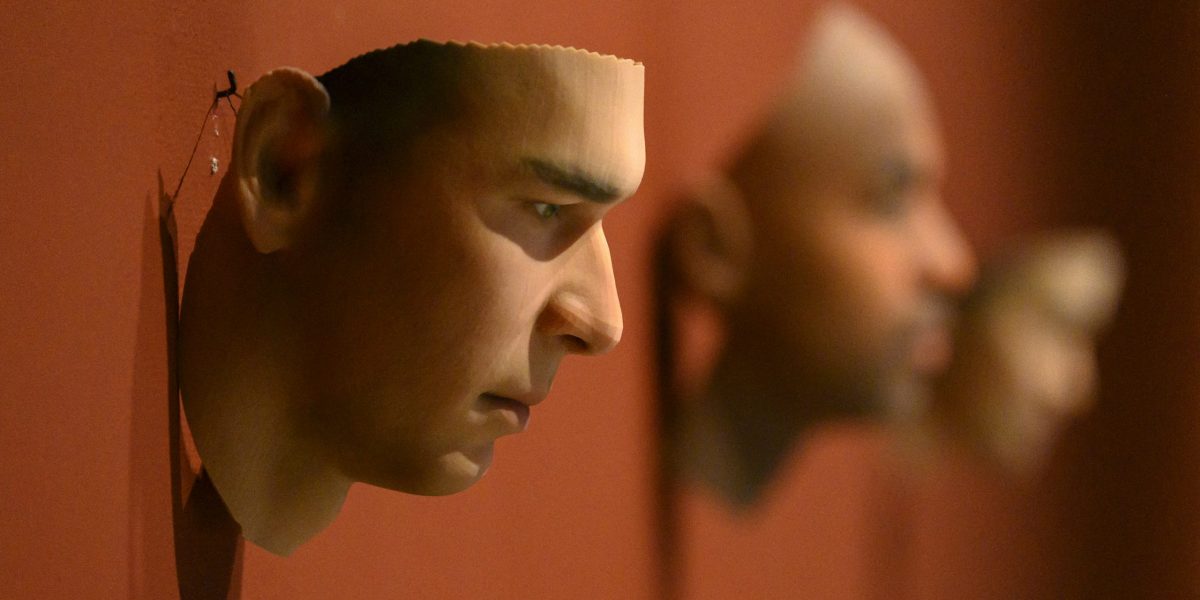

The traditional boundary between body and mind, in which the former is the vehicle for the latter, had already been undermined by the rise of information technology in recent decades. Surely it will be possible one day to place the human mind on another substrate? The body occupies a central yet ambivalent position within the museum’s ‘Posthuman’ theme. It functions on the one hand as an interface between human and technology, making it the nexus of all manner of improvements. On the other, it creates the impression of the body as something that needs to be conquered. This implies that posthumans will eventually have to leave their earthly substrate behind or – in the case of artificial intelligence – create something that transcends or even replaces humanity. The contours of the posthuman are becoming increasingly blurred as it is absorbed into a nexus of biology and technology, culture and nature.

Experimental and speculative

All this might sound rather theoretical and abstract. Arguably because this is inherent to the subject but perhaps also because my writing skills aren’t up to the task. Which is one of the reasons I wanted to present the theme in the form of an exhibition: as a curator, that’s my real forte, after all. Nevertheless, many of the future-oriented designs in the BodyDrift exhibition are experimental and speculative by nature, which risks giving visitors the impression that the ‘Posthuman’ is something well beyond their own everyday experience. To highlight the relevance of the subject, we have therefore included a newsfeed in the exhibition. Three screens – one for each group of works – have been spread around the gallery to show montages of news reports from all over the world. These show just how much the developments we explore are already impacting society.

The future is now!

The discoveries and inventions covered in these reports are amazing and until recently would have been unbelievable. What the news items show above all is that even the most experimental works in the exhibition are not as speculative as they might appear at first sight. Fact is often stranger than fiction. There are images of people who have integrated technology in their bodies to a far-reaching degree in the form of prostheses, whether or not for medical reasons. Other feeds show how when it comes to surveillance, we’re effectively living under Big Brother already, while artificial intelligence can beat us nowadays at pretty much any game you care to name. These are just a few of the many examples demonstrating that the ‘Posthuman’ is far from science fiction. That icon of the Enlightenment – ‘Vitruvian Man’ (of course he’s a man…) is long since dead and buried. [‘Send not to know for whom the bell tolls. It tolls for thee’.]

From being to becoming

But there’s no such thing, obviously, as the future: developments are in flux and the times are constantly changing: certainly in the posthuman realm, where ‘becoming’ takes precedence over ‘being’. This is why the following articles will, as I have said, each explore a specific aspect of the Posthuman story, with the changing body often serving as the starting point. The Covid-19 crisis will feature too: I feel that it has a lot of posthuman facets and that it has definitely brought a number of related trends to the surface. For now, though, I will round off with a quote from the Observer journalist Rowan Moore’s review of the exhibition The Future Starts Here at London’s V&A Museum in 2018:

‘The interaction of the material and the virtual can work in at least two directions. The physical – and especially the human body – can be augmented, empowered and given unprecedented capacities. Or it can become a negotiable, fragile, decreasingly essential vessel for the play of networks and systems within it and without.’

Fredric Baas

Curator, Design Museum Den Bosch