Titi Finlay is a London based content creator, sneakerhead and sneaker activist working with footwear brands to create equality. For the Third Floor she tries to answer the question: why can’t sneakers be gender neutral?

It’s 8am on the 30th July 2021, and I’m on the Nike SNKRS App ready to part with £120 of my hard-earned cash. For the last four years, I’ve been hunting down a pair of Persian Violet Air Max BWs in my size – with no avail – but today, finally, I have the chance to purchase the 2021 re-release.

08:00 – I get the notification.

OK, open the app.

Click on product.

Palms sweating, heart beating (ah, that familiar sneaker drop feeling).

But wait – why does the sizing start at a UK5.5?

This has to be some kind of mistake.

I frantically Google the size run to find out that they won’t be releasing smaller sizes in this colourway.

My heart sinks.

And yet, this is a routine I’ve become all too used to. As someone with smaller feet (UK4 / EU37) I regularly miss out on important sneaker drops due to the size run. Brands typically favour standard men’s sizing (UK5.5 – UK12) making consumers who sit either side of that spectrum feel like an afterthought. And we’re not just talking general release pairs either – this happens with key releases that we sneakerheads save up and get excited for months in advance. Travis Scott and Off-White collabs, New Balance classics, iconic Air Jordan and Air Max retros will release in standard men’s sizing, while women (or simply those with smaller feet) are left with three options:

– Buy the Grade School version – knowing the shoe will be made with a slimmer fit, cheaper materials and missing important design features.

– Wait to be served a pastel/chunky version of the same shoe.

– Miss out completely.

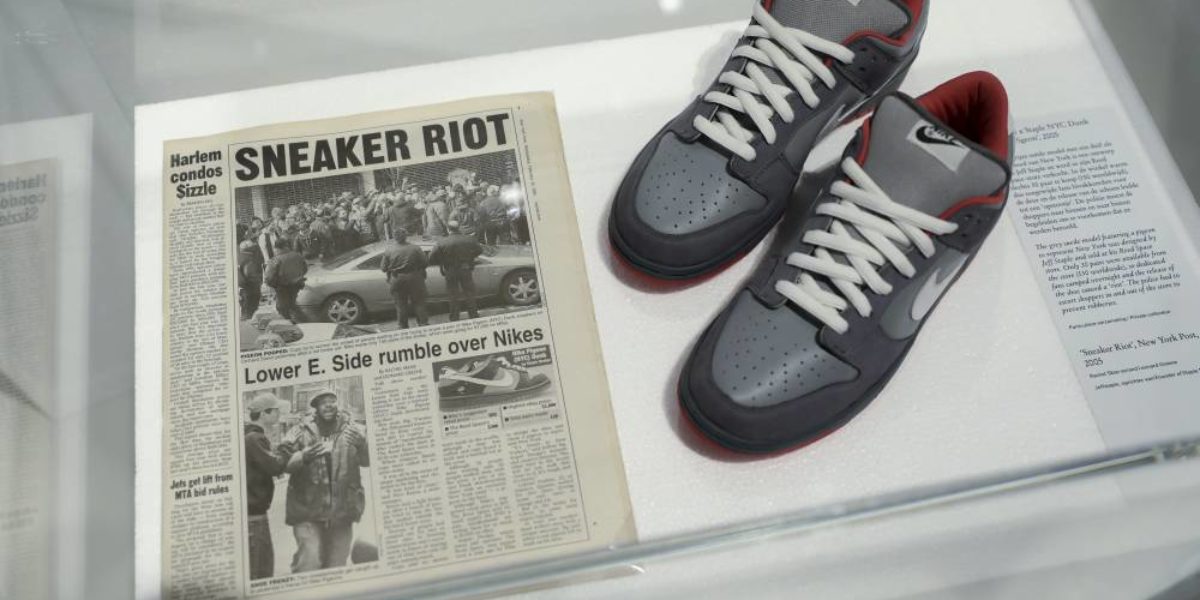

A prime example of option two was during the early days of the Nike Dunk resurgence back in 2020. While male consumers were served coveted retros from the original ‘Be True to your School’ pack, females were marketed the ‘Dunk Disrupt’ – a pastel-hued, chunky, recrafted version of the silhouette. While this new take was well-received by the masses and high street shoppers, it was another sting for veteran female sneakerheads fed up of being offered a ‘pink it and shrink it’ version of the sneakers they actually wanted. To make matters worse, some male sneakerheads then expressed disappointment that they couldn’t buy into the pastel colourways due to the women’s-only sizing.

It’s clear consumer tastes are moving in a gender neutral direction – so why do brands continue to sell us gendered products?

Dit bericht op Instagram bekijken

It was this realization that drove me to create the graphic ‘WE DON’T NEED WOMEN’S EXCLUSIVES. WE NEED INCLUSIVE SIZING.’ which I posted on my Instagram and, to my surprise, re-shared over 8,000 times reaching 32,000 accounts worldwide. The collective frustration around this issue united the sneaker community, particularly women, and sparked a movement that has been picked up by publications like Vogue and Highsnobiety, forcing brands to stop and listen. Since then, Instagram accounts like @_womeninsneakers, @sneakersisterhood, @sheakermag and @sneakersbywomen have continued to push for more representation and more inclusivity, forcing visible and actualised change – women are now at the forefront of sneaker culture.

But when you strip back the storytelling and campaigns, we’re still facing the same problem: the product itself is still not fully inclusive.

Two years have passed since I shared that first graphic, and during that time I’ve been lucky enough to have conversations with designers, merchandisers and marketers from the world’s leading brands. I’ve learned that for the sneaker industry to reach a truly gender neutral space, it comes down to three main elements: colour, sizing and marketing.

Footwear Designer Cesar Idrobo insists the latter is the biggest obstacle of them all. Designing a full size run that caters to all is not the biggest challenge – marketing is what truly obstructs most brands’ design departments. When it comes to gender neutral sizing, it CAN be done but marketing departments and merchandisers are ultimately who decide if it WILL be done. Idrobo references the original ‘One Size Fits Many’ campaign around the Nike Air Presto, which ditched the standard numerical system in favour of an XXS – XL format (each size spanned two numerical sizes). The departure from standard sizes helped people choose the most comfortable fit, but it also helped remove gender from the equation. He suggests that “sizing is often psychological” (most people can actually fit into a range of sizes and tend to size up or down depending on how they want the sneaker to look). For the Presto, it made sense to market novelty sizing, but what about every other sneaker?

According to Idrobo, there is less demand for smaller sizes with most people falling within the bracket of UK5 – UK12, which explains the standard size runs for most footwear. However, when brands know that major hyped releases will sell out, no matter the size, it begs the question: why wouldn’t they release them in a full size run? Independent footwear designer Leon Avery explains that creating smaller sizes requires ‘opening the mold’ meaning metalwork for new soles must be created (reproducing lasts is the costly part). As a small brand, he has to consider the Return On Investment if there’s less demand on small sizes, but for mega brands, the costs are so insignificant it would be silly not to serve the demand of all their customers.

Or so you might think.

The latest Travis Scott Air Jordan 1 Low caused uproar when sneakerheads realised it wouldn’t release in smaller sizes, creating a stir on social media and driving demand as a result. It’s no coincidence that the Air Jordan 1 Low silhouette has since become extremely popular in general release colourways – it’s a common tactic for brands to use a hype release to create demand for a silhouette and then drop multiple general releases shortly after. But somewhere in that very precise method is a messy oversight with sizing.

Granted, inclusive sizing is no easy feat. Avery mentions the challenges he had designing a shoe that didn’t restrict the cuneiform bone (around the lacing system) and had a wide enough fit to provide comfort for both male and female foot shapes, while Nike’s Air Max Creative Director Dylan Raasch says that one of their biggest design obstacles is the difference in width between the male/female ankle bone. After all, sneakers are for practicality and comfort, and for brands with multiple silhouettes across lifestyle and performance, getting the right fit for everyone can be tricky.

But size isn’t everything. For female consumers, one of the most frustrating elements of sneaker shopping is the choice of colour. Historically, brands have applied the infamous ‘pink it and shrink it’ approach to sneakers marketed to women, while traditionally ‘masculine’ colourways are always available to men. Speaking to Raasch, he mentions that the new Nike Furiosa (a Women’s Exclusive) has actually had more demand from male consumers, particularly in the pink and pastel colourways. Meanwhile, female sneakerheads are moving away from the Instagrammable pastels and looking for more muted, neutral pairs. Gender norms are a thing of the past, and luckily, brands are starting to take note – Nike’s 2022 Valentine’s Day Dunk was pink, frilly, and available to all in a full size run.

In fact, there’s a lot of brilliant innovation in the sneaker world right now – we’re en route to a more sustainable and more inclusive industry overall. Yeezy are making strides with versatile colourways, materials and silhouettes available in full extended sizing – by looking at sneakers as pieces of art rather than products for a specific consumer, they have been able to transcend gender completely. And with the Metaverse fast becoming a (virtual) reality, brands like Nike, RTFKT and Flowers for Society are designing NFTs and ‘Cryptokicks’ that don’t need to physically fit anyone at all.

As a female sneakerhead, I like to think my days of feeling left out are numbered. Consumers are speaking up, and gradually, brands are actioning change. So to answer my own question, why can’t sneakers be gender neutral? The truth is, they can – and I hope I get to witness that become a reality in the near future.