So Posthuman (2): Capsules: the ‘bubbles’ of the Sixties

This column by Fredric Baas is the second in a recurring series. In it, the curator shares his insights about all things ‘posthuman’.

What do you think of when you hear the word bubbles? Champagne or blowing bubbles? Or do you perhaps think of the ‘filter bubbles’ that are getting more and more attention these days? In the sixties and seventies, designers were busy with a completely different kind of bubbles. In what is also known as ‘the Inflatable Era’, inflatable architecture was manufactured as a prerequisite for a new, nomadic way of life. Space travel served as the inspiration for these capsules. However, are these high-tech hide-outs post-human or not?

The title of this series of columns, ‘So Posthuman’, suggests that the various manifestations of this paradigm shift will be touched upon, if not explained. However, this is not always a question of identifying what is posthuman, but sometimes precisely what it is not. In the resulting contrast, the contours of what is posthuman become more clearly visible. In this second column, I will focus on an aspect of the work of the Austrian architects, designers and artists in the exhibition Radical Austria – Everything is Architecture that is decidedly not posthuman.

1. Hans Hollein, Mobile Office, 1969. Still from ‘The Austrian Portrait / episode 19: Hans Hollein’, production of Telefilm commissioned by ORF. Courtesy of Generali Foundation Collection – permanent loan to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg.

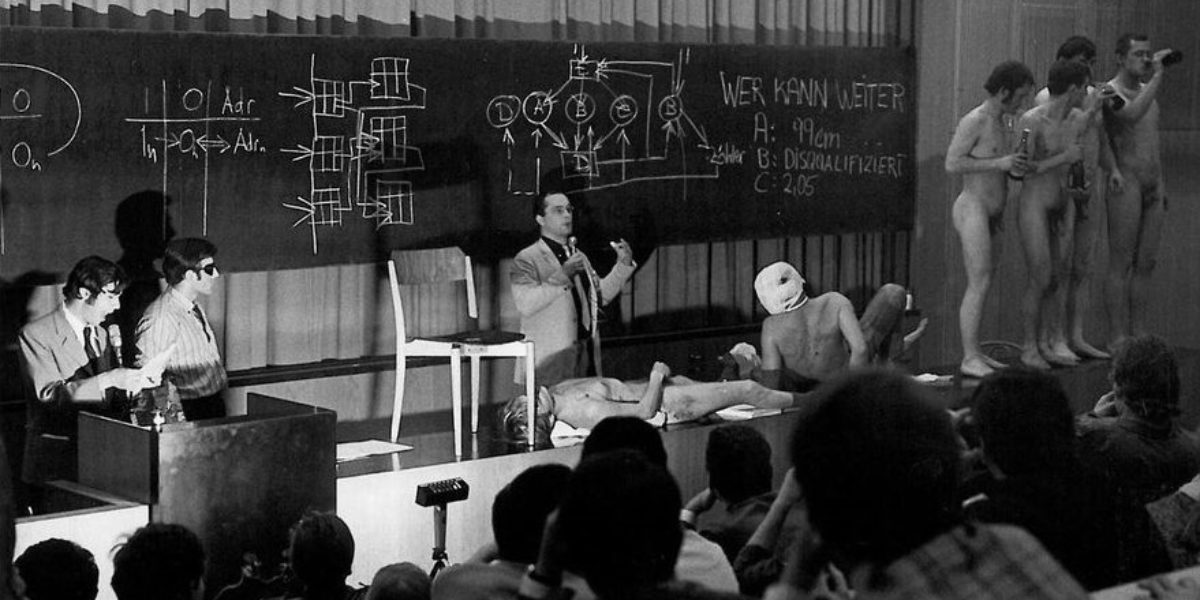

In the previous column I discussed the’predictive powers’ of these Austrian designers. In addition to signalling future developments, they naturally also reflected on contemporary events. The range of phenomena and trends that serve as sources of inspiration in the turbulent sixties seems endless; the rise of mass media and youth/counterculture, experiments with pharmaceuticals, changing sexuality and feminism, environmental issues and new materials and techniques. And last but certainly not least: space travel.

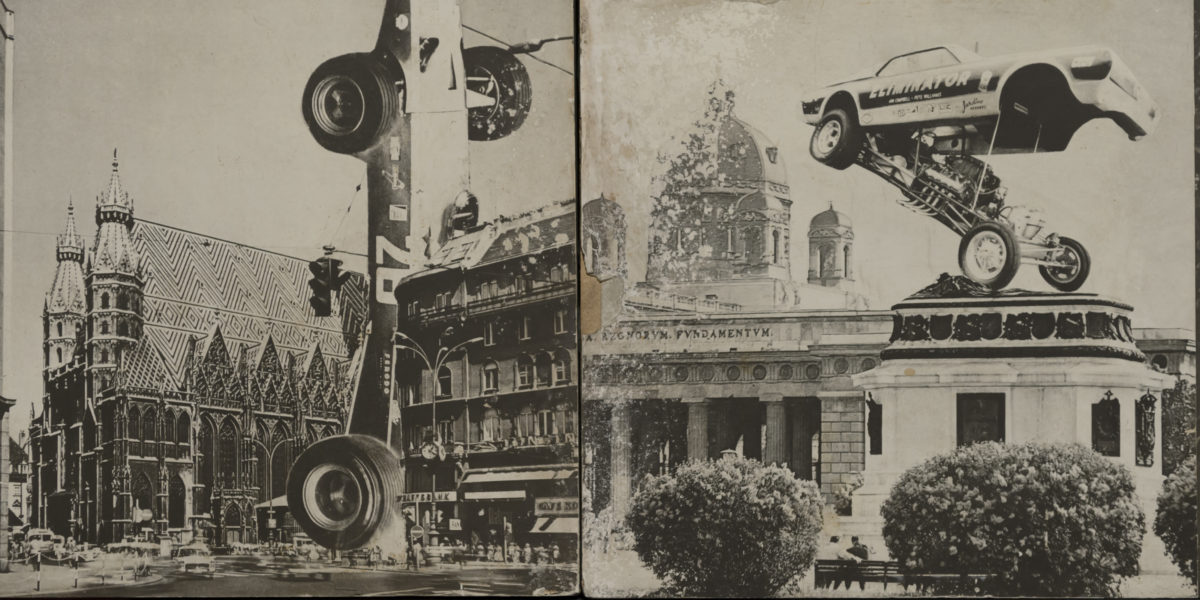

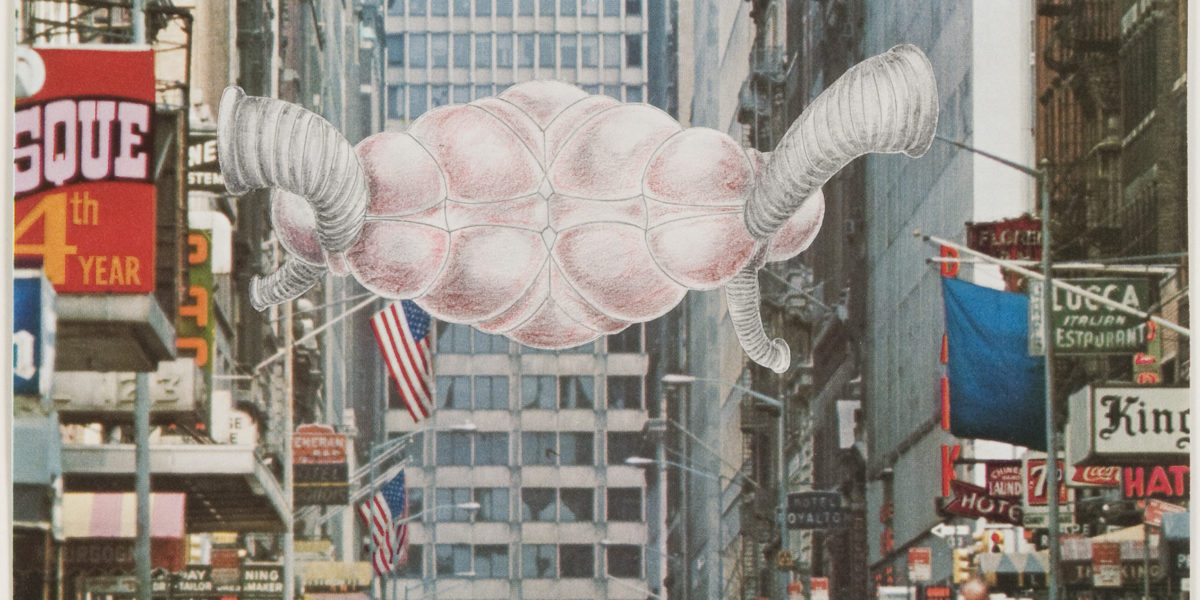

Space travel, and in particular the capsules and suits used for the first manned space flights, had a major impact on artists, architects, and designers worldwide and certainly on ‘the Austrian Avant-Garde’. References to space travel and specifically to the archetype in that context, the capsule, can be found with almost all participants. The capsule appears in various guises in the work of Walter Pichler, Hans Hollein (img. 1), Raimund Abraham, Angela Hareiter and certainly also Coop Himmelb(l)au (img. 2).

2. Coop Himmelb(l)au, various suits and capsules including: models for Villa Rosa and The Cloud, 1968 and images of Villa Rosa and White Suit, 1969. Collection Coop Himmelb(l)au. Photo Peter Tijhuis.

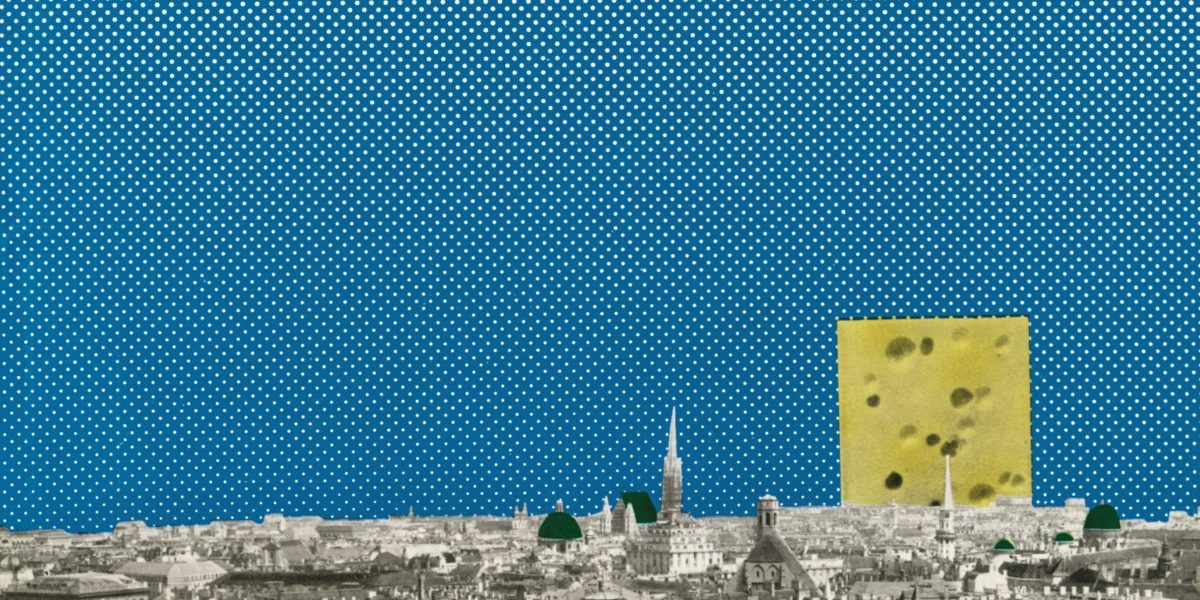

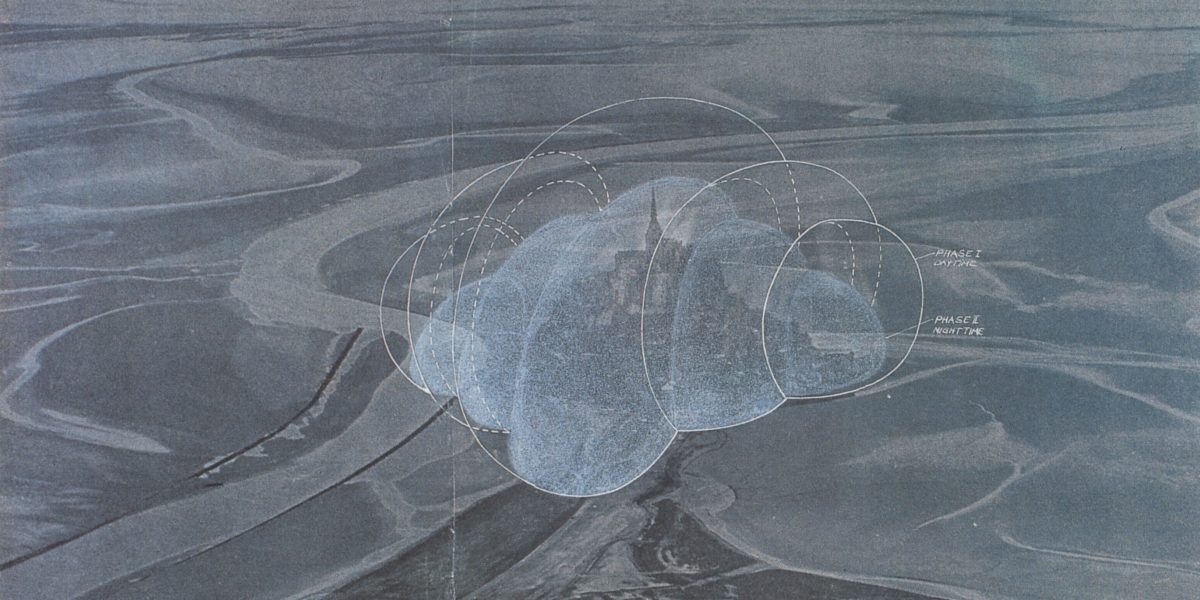

The most telling and in any case most elaborate example is Haus-Rucker-Co’s Mindexpanding Program, running from 1967 to 1971. Within this comprehensive, long-term project, they initially designed helmets, glasses and clothing (img. 3). he next step is a piece of furniture in which a man and a woman take place under a kind of helmet in which light effects are played. Finally, a number of inflatable capsules are actually manufactured (img. 4). With the exception of the Yellow Heart, all versions can be seen in the exhibition. The idea was that people could sit or lie for a while in these capsules, isolated from their surroundings and temporarily absorbed in an alternative reality.

3. Haus-Rucker-Co: Laurids Ortner, Günter Zamp Kelp & Klaus Pinter met Environment Transformers, 1968. Collectie MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, Wenen. Foto Gerald Zugmann.

In an article on architecture and sustainability by Beatriz Van Houtte Alonso that was published in De Witte Raaf at the beginning of this year, an interesting connection is made in that respect.* Van Houtte Alonso discusses, among other things, the fact that the energy-intensive, technology-regulated and sealed building as we know it today is a recent invention. In this context, she cites Peder Anker’s From Bauhaus to Ecohouse (2010). In it he describes in her words:

“…how our current Western conception of energy-efficient building is directly modelled on 1960s space travel. Prominent ecological designers, such as Buckminster Fuller, considered closed ecosystems of space capsules as dwellings that did not burden the environment. According to Anker, this technocratic approach led to alienation from cultural and social values and, paradoxically, from the natural environment itself. In that respect, contemporary hermetic construction is building as if we were already living on Mars: literally and figuratively planting isolated entities in the middle of an unknown and hostile environment, as it were.”

The preoccupation with the principles and design principles of space travel, of which the capsule is a prime example, have thus given rise to an architectural mind-set that, from its obsession with high-tech, leads to both alienation and waste, but is still dominant.

4. Foreground: Haus-Rucker-Co, Mind Expander II, 1969. Collection Laurids & Manfred Ortner, Haus-Rucker-Co archive. Left: Haus-Rucker-Co, Balloon for Two, 1967. Collection Günter Zamp Kelp. Photo Mike Bink.

The idea of isolation to which all the different capsules in the exhibition refer is decidedly non-posthuman. Isolation implies a clearly separated inside and outside. Such a form of dualism is an essential characteristic of Cartesian Enlightenment thinking. This thinking in separate and opposing concepts; object/subject, culture/nature, human/non-human is exactly what posthumanism is trying to dismantle.

Of course, capsules are not inherently good or bad. They are often necessary to allow our fragile bodies to visit harmful environments or areas. The distance and separation they create are necessary but also regrettable. That they, like the sailing ships of old, facilitate our urge for exploration and thus bring us into contact with the unknown can be seen as positive. However, in the slipstream of exploration often followed exploitation. And the created ‘distance’ was very useful…

The capsule-like houses and offices in which we find ourselves on a daily basis may not directly lead to exploitation, but they do isolate us from our surroundings. This separation and the associated sense of alienation encourages the exploitation of the earth. In turn the worsening living conditions resulting from climate change – heat waves, forest fires, rising sea levels – threaten to create a feedback loop which only increases the urge to protect ourselves.

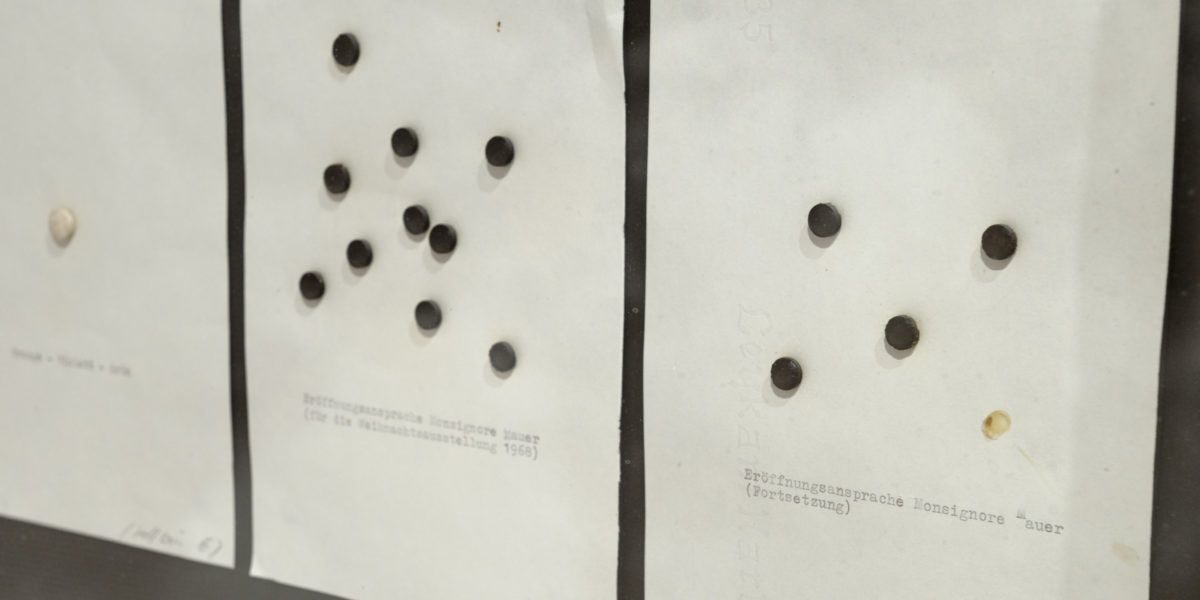

5. Hans Hollein, Architekturpillen, Non-physical Environmental Control Kit, 1967. Private archive Hans Hollein. Photo Ben Nienhuis.

Perhaps we should seek refuge in a different kind of capsule that is featured in the exhibition. I am referring here to Hans Hollein’s Architekturpillen, in which he ingeniously applies the slogan of the chemical giant Dupont, “Better living through chemistry”, to architecture (img. 5). The experience that these pills are supposed to evoke – hypothetically speaking – is considerably more posthuman. The ‘imaginary architecture’ evoked would not pollute either, or the sewage at most.

* Van Houtte Alonso, Beatriz. Negen reflecties over architectuur en duurzaamheid. De Witte Raaf, nr. 209, p. 23-25, 2021. Find the online version here.