So Posthuman (3): Monstrous humans and human monsters

This is the third column in an ongoing series, in which curators share their thoughts on all things ‘posthuman’.

You only have to pick up a Gothic novel or turn on a horror film to notice the Gothic obsession with the human body. Limbs are torn off and grow back; decomposing corpses dig their way out of the grave; and flesh-and-blood human beings are transformed into hideous monstrosities or possessed by voracious demons from another world. Nothing is safe: the way we look, our sex, gender or sexuality, our health, our physical integrity or even our mortality. And if we’re no longer human… what are we exactly?

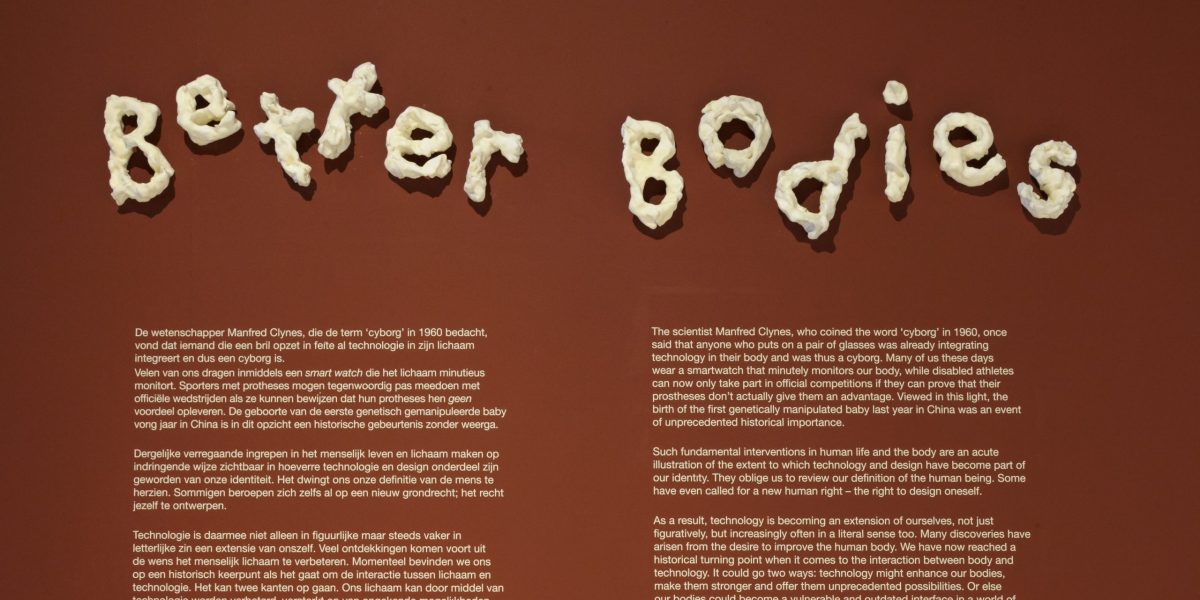

The theme of posthumanism, which is all about looking beyond our human limitations, constantly raises this same question. What I want to explore in this column is what the Gothic and the ‘posthuman’ have in common.

Within the Gothic imagination, nothing is what it seems: a monster is never just a monster. The boundaries between body and soul or between death and life itself are frequently called into question. Take ghosts or phantoms – beings with no physical body but which can still slam doors, cause candles to flicker or loom up in your bathroom mirror. Or vampires, which are neither dead nor alive, human nor beast. Creatures like these make us less certain about what belongs where and what doesn’t. According to the cultural critic and gender researcher Judith Halberstam, the Gothic fascination for the unheimlich or uncanny is eminently modern:

“Gothic […] marks a peculiarly modern preoccupation with boundaries and their collapse. Gothic monsters, furthermore, differ from the monsters that come before the nineteenth century in that the monsters of modernity are characterized by their proximity to humans.” — Judith Halberstam, Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters (1995)

All this swiftly evokes associations with posthumanism, which explores the human being’s limits: the ways in which our bodies can be modified or even transcended. For some, this process is a noble goal. Yet it also raises profound insecurities, fears and questions, which translate readily into Gothic images and associations. In another of her books, Halberstam describes the posthuman body in the following terms:

“The posthuman body is a technology, a screen, a projected image; it is a body under the sign of AIDS, a contaminated body, a deadly body, a techno-body; it is, as we shall see, a queer body.” — Judith Halberstam en Ira Livingston, “Introduction: Posthuman Bodies”, in Posthuman Bodies (1995)

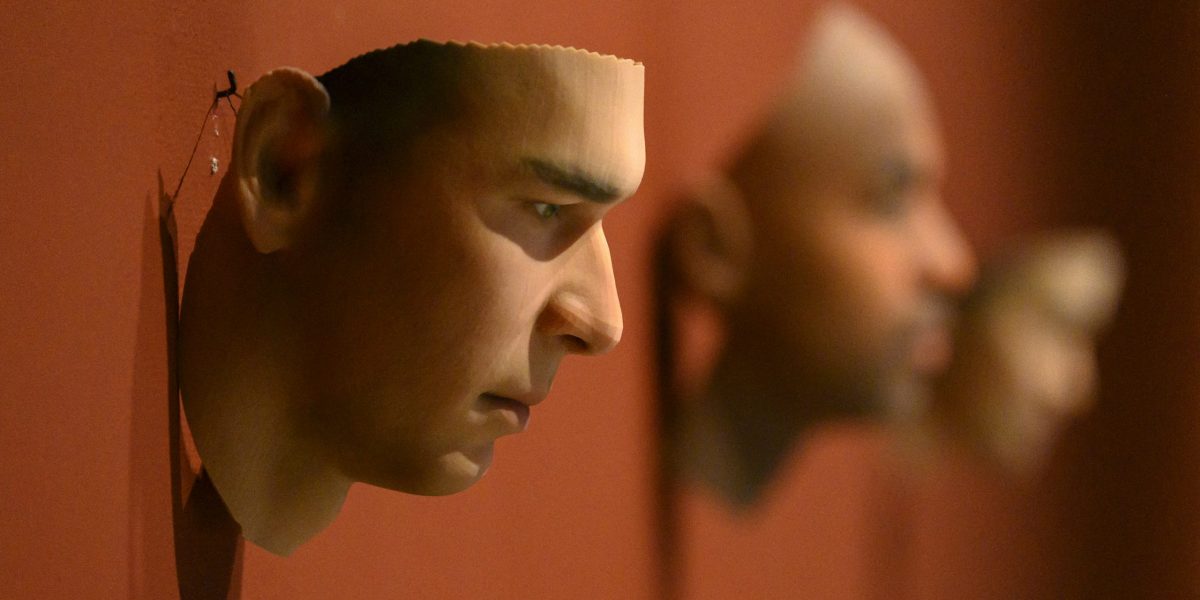

Her list alludes to liberation (technology, queer) but also to inauthenticity (screen, projection) and even damnation (infection, death). Posthumanism upends our notions of security and certainty. The design of the new human is exciting, yet it can also be downright creepy. Take the futuristic yet perverse Biomechanoids of the Swiss designer HR Giger, as featured in the exhibition GOTH – Designing Darkness.

Works by HR Giger in the exhibition GOTH – Designing Darkness. Photograph: Chantal Lenting for Design Museum Den Bosch.

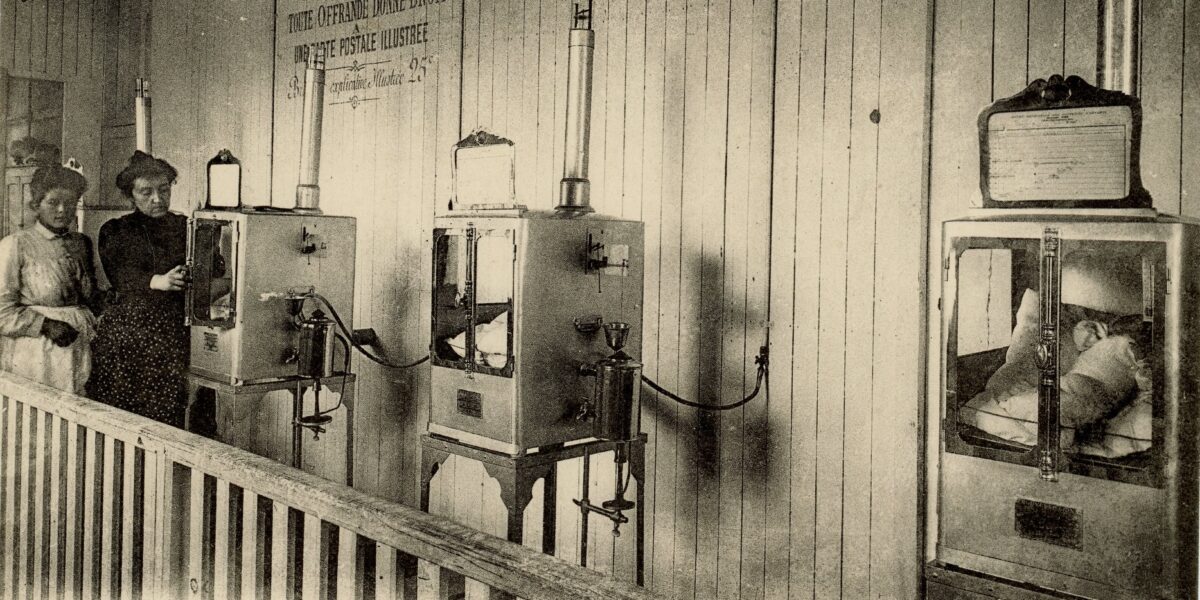

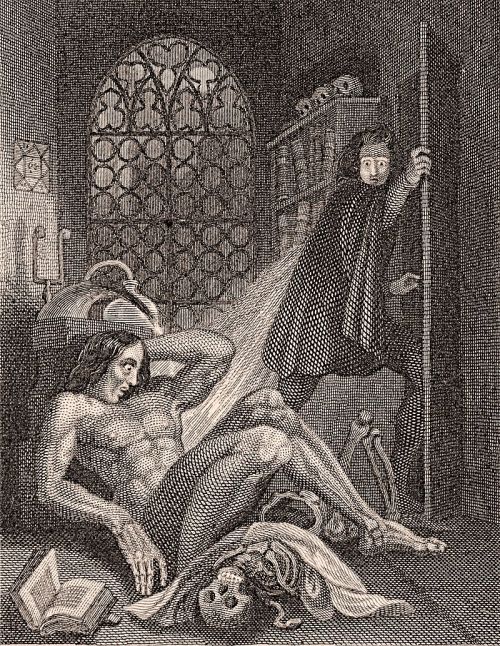

It’s no coincidence that many Gothic novels refer to the technological and scientific debates of their time, the most famous and influential example, of course, being Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). In her iconic book, a young scientist called Victor Frankenstein sets out to design a living human being for himself. At the first sign of life, however, he immediately realizes he has gone too far:

“How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe, or how delineate the wretch whom with such infinite pains and care I had endeavoured to form? His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful! Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath […].” — Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus (1818)

The creation of a new kind of human being in Frankenstein marks the breaching of ethical, moral, and ‘natural’ boundaries. It is precisely the monster’s not-quite humanity that makes it so terrifying both to its creator and to us. Shadowy spaces like this between fear and expectation are the genre’s domain par excellence:

“Always present in the Gothic is this: two things that should have remained apart – for example, madness and science; the living and the dead; the living and the dead; technology and the human body; the pagan and the Christian; innocence and corruption; the suburban and the rural – are brought together, with terrifying consequences.” — Gilda Williams, “How Deep Is Your Goth? Gothic Art in the Contemporary”, in The Gothic: Documents of Contemporary Art (2007)

The horror of blurring boundaries and the associated technophobia (as described by Anthony Mandal in his essay ‘Gothic 2.0: Remixing Revenants in the Transmedia Age’, 1995) is therefore a typical theme for the Gothic. Which is not to say that the genre does nothing but wag an admonishing finger at anything considered to be ‘other’. Gothic images and stories can be found throughout our popular and wider culture and in each place, they have developed in different ways. The result being that monsters can be scary, romantic, funny, corny or all of these at once. Gothic novels and horror films might convey a conservative message or just as easily highlight the horror of injustice.

Posthuman horror sees us transcending our human bodies and merging into something new – something that, viewed through a Gothic lens, can also be a form of freedom. Goth subculture, for example, nuances the time-honoured ‘good and evil’ of the Gothic novel. Goths identify with the outsider. They rise above their everyday selves in an almost posthuman way, preferably into a world beyond the stifling character of everyday life. The Cybergoth offshoot goes so far as to explicitly embrace the fusion of human being and technology, taking its stylistic cues from cyberpunk films like Tron, Blade Runner and The Matrix.

Replicant Pris (Daryl Hannah) and genetic designer J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson) in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982). PictureLux / The Hollywood Archive / Alamy Stock Photo.

The final link with posthumanism is, perhaps, the most obvious one: the Gothic is also subject to the increasing influence of new communication technologies. According to Mandal, the genre’s characteristic mix of real and fake is ideally suited to flourish on the internet. We can copy originals and remix them to create a new image, a new style, a new story. Social media allows anyone to transform themselves into a vampire bat, even if they are mousy in everyday life.

Real or fake? Creepy or familiar? Deadly serious or ironic? It is precisely the uncertainty and instability of posthumanism that makes it a Gothic phenomenon par excellence.