This column by Fredric Baas is the first in a recurring series. In it, the curator shares his insights about all things ‘posthuman’.

Posthuman; once your eyes are opened you see it everywhere. But what is it exactly? The exhibition BodyDrift – Anatomies of the Future, which was on view last year in Design Museum Den Bosch, attempted to answer this question in relation to the human body. On the online platform De Derde Verdieping that was created in connection with this project, various authors have also elaborated on this broad theme. I myself have been immersed in the subject for such a long time that I look at almost everything through this lens.

The saying ‘To someone carrying a hammer everything is a nail.’ seems to apply to this situation to some extent. Even so, in this first of a series of columns I’ll attempt to further explain what Posthuman means by pointing out subjects or developments that I think exemplify it. To begin with I’ll be focussing on projects related to the museum and our own angle of approach in this regard; the human body. So I hereby pick up the hammer again. And please forgive me my two left hands.

In his book ‘Dude, Where’s My Jetpack?’ author Daniel H. Wilson asks why we still do not have the miracles we were promised in the science fiction films of yesteryear. Often – despite many failed attempts – this is a question of feasibility and safety. As the jetpack from the title nicely illustrates. Implicitly, the book also reveals how the high expectations for the future reflect the preoccupations of the era in which the fantasy was conceived.

Each image of the future is first and foremost a reflection of the times. For example, the very personal diplomacy of Captain Kirk from the first Star Trek series reflects the love-and-happiness vibe of the Sixties. The two power blocks from the first Star Wars series are so exemplary of the Cold War that President Reagan in turn seems to have unconsciously co-opted the movie’s vocabulary when he referred to the Soviet Union as an ‘evil empire’.

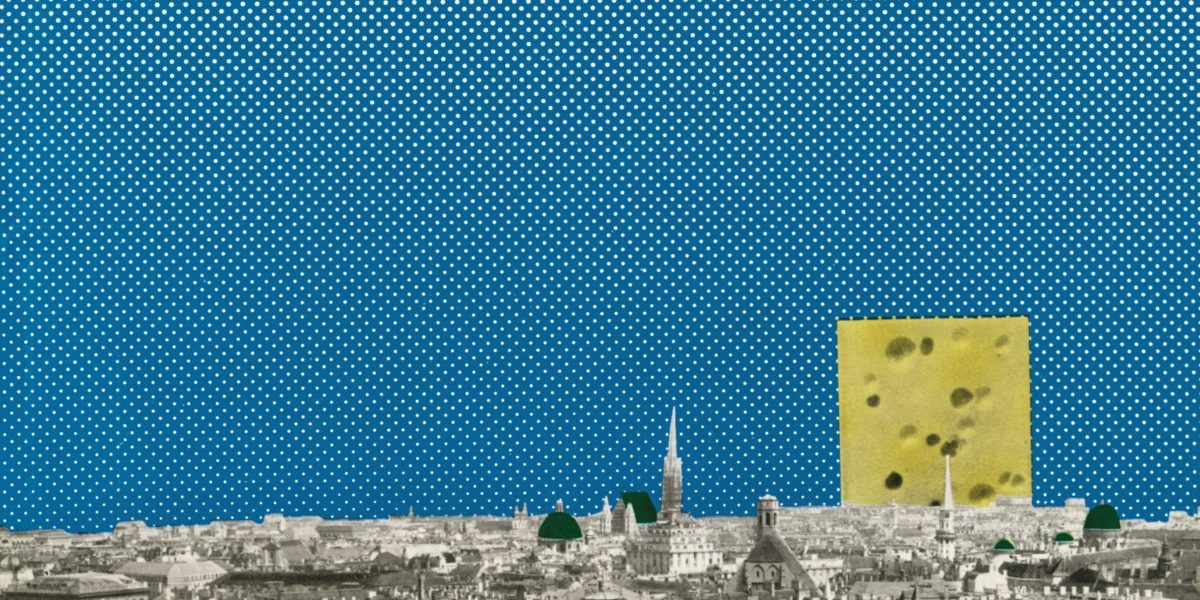

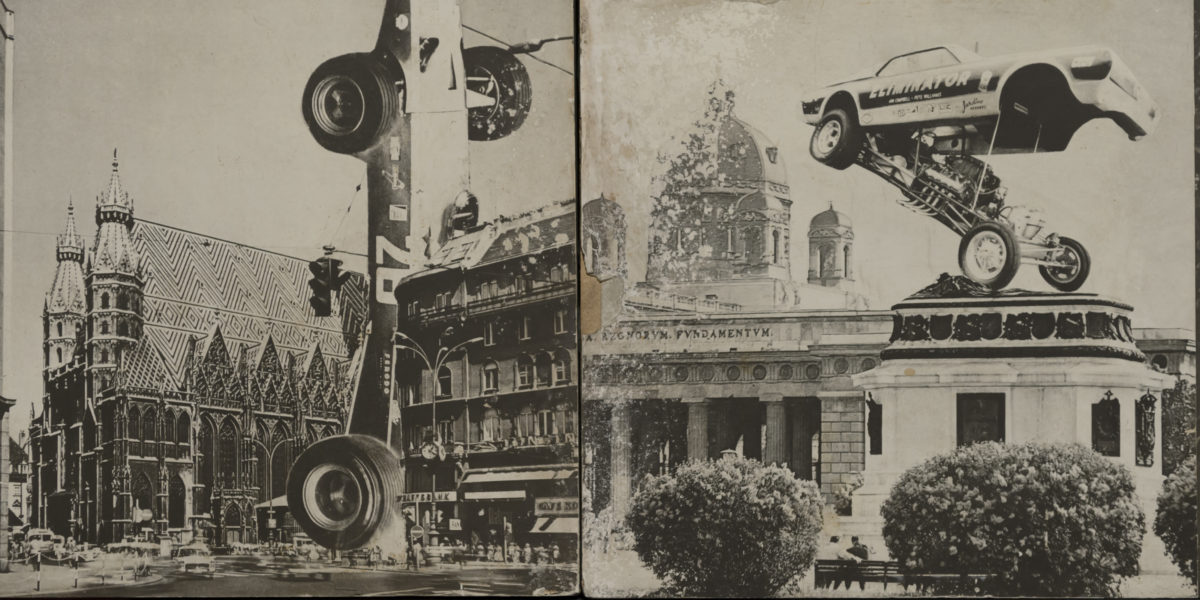

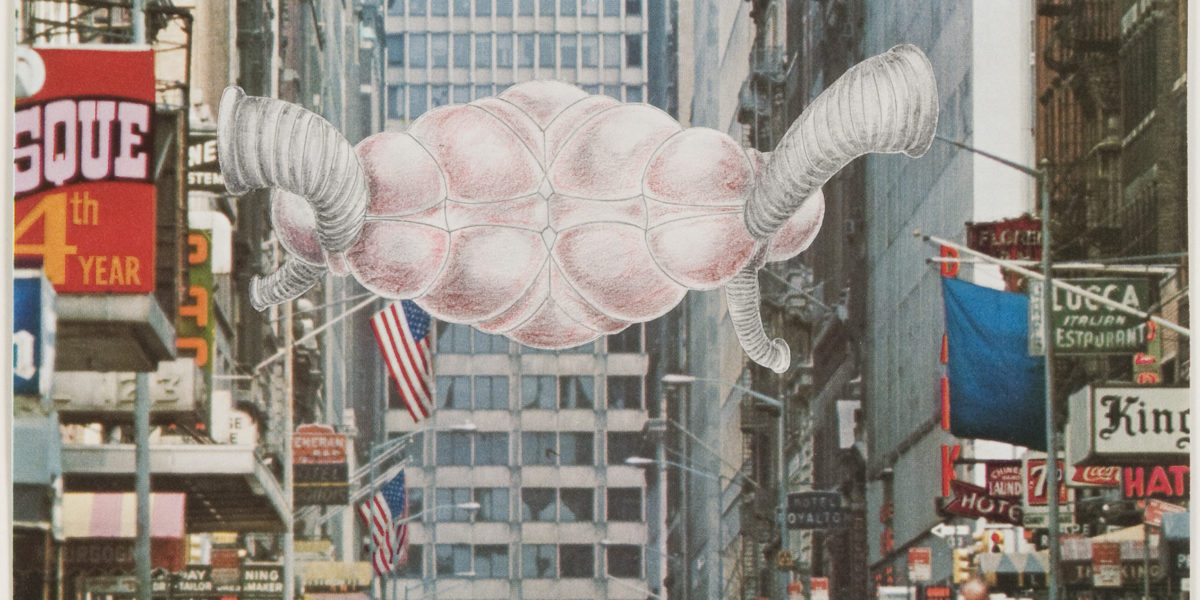

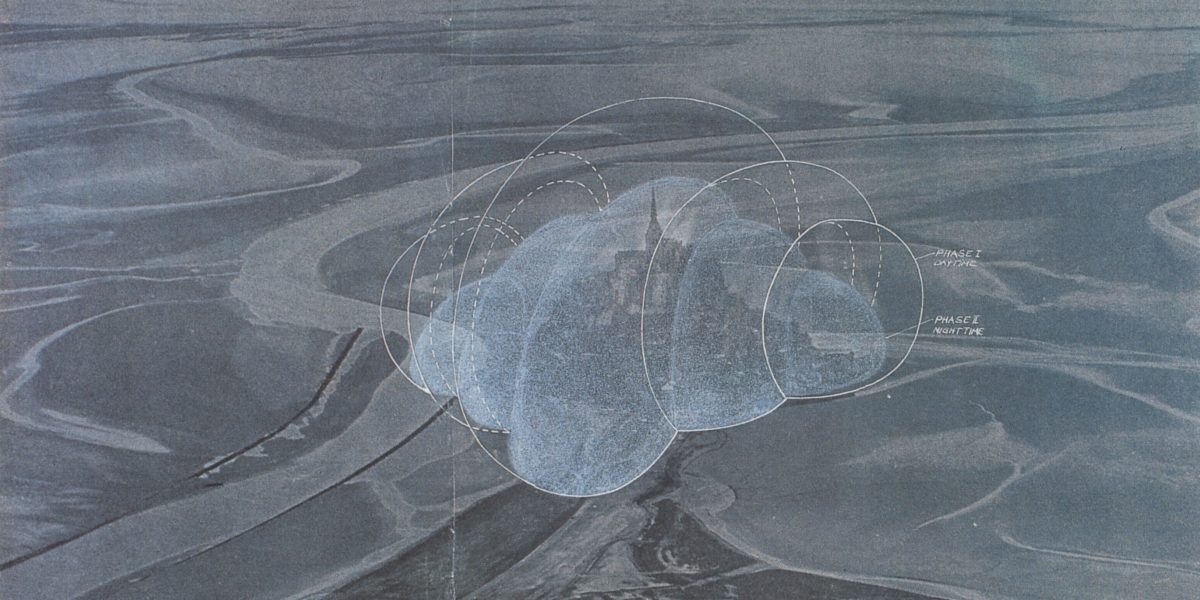

In the work of individual designers and design collectives from Austria in the 60s and 70s that is now on display at Design Museum Den Bosch in the exhibition Radical Austria – Everything is Architecture something similar is going on. Many predictions – although their projects were not necessarily intended that way – of the designers and architects included have not come true. Inflatables – forgive me the metaphor – never really took off.

And we still don’t have Holleins architecture pills either. But they are powerful and, in their time, radical manifestations of a desire to profoundly change architecture and through it the world. And in doing so, a number of the participants did seem to foresee keenly was the changing role of, and views on, the human body.

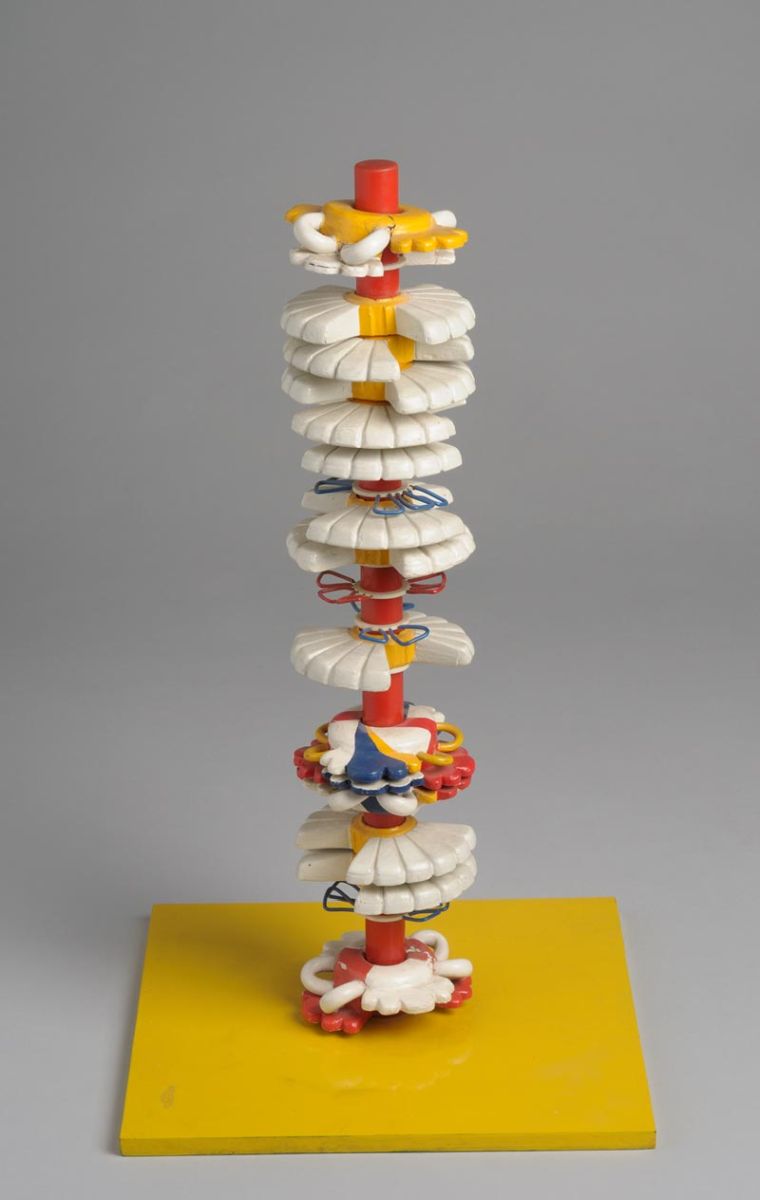

Haus-Rucker-Co, Wohnraum im Raum, 1967. Collection Lentos, Linz. Photo by Mike Bink.

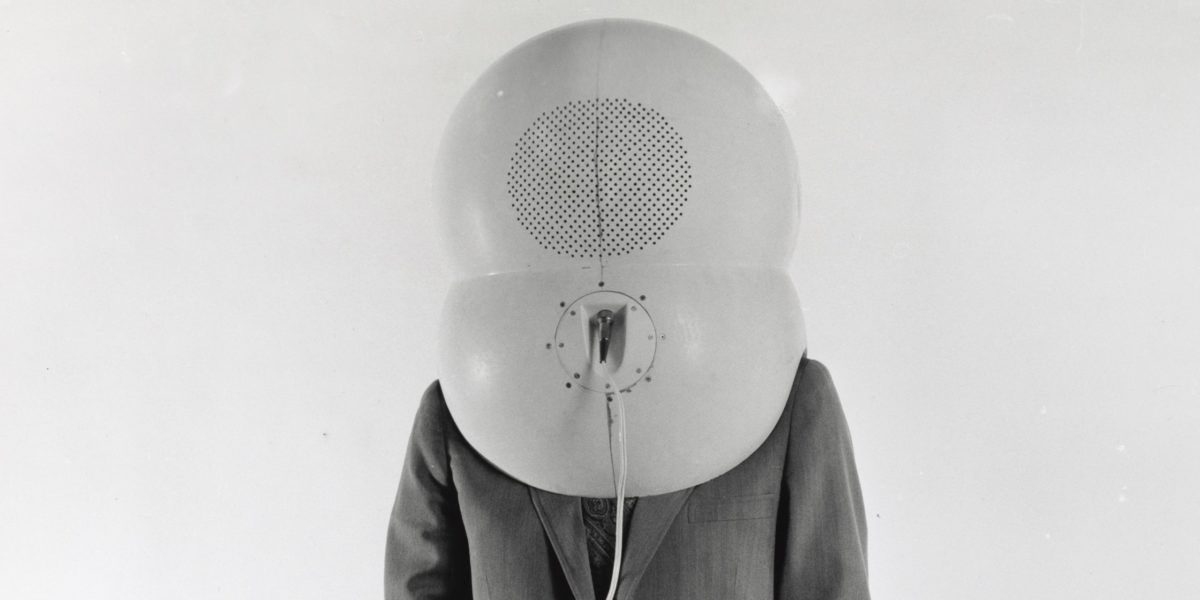

For instance, with their wearables, Walter Pichler and Haus-Rucker-Co already seem to be alluding to the world in which we now live. Our present moment is dominated by developments that are being classed as posthuman. Which would make the aforementioned makers proto-posthumans. That is perhaps too bold a statement but aspects of what we now call posthuman can certainly be identified in some of the works included in the show.

Pichler’s helmets are striking, early examples of the use of (wearable) technology to counteract the effects of that same technology. They isolate the wearer from the outside world and the barrage of mass media.

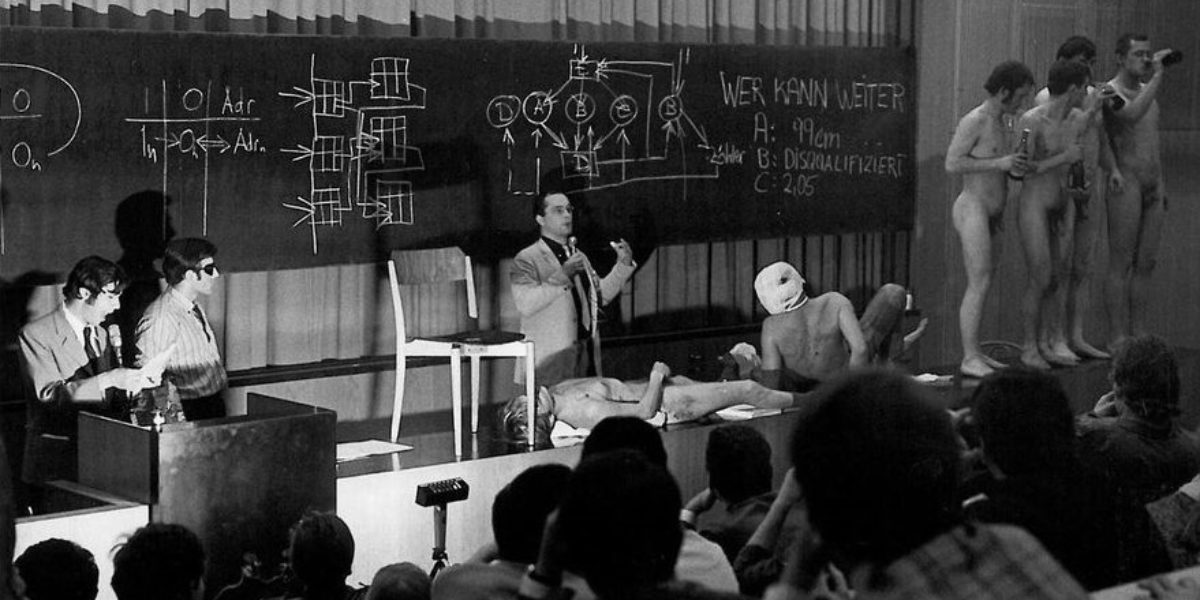

Haus-Rucker-Co’s Mind Expanding Programme is obviously a child of its time in the way it uses light, sound, colour and environments to evoke a psychedelic experience. At the same time, the desire to transcend the human sensorium by seeking out its limits is very much akin to the anti-anthropocentric stance that defines posthuman thinking.

Haus Rucker-Co, Mind Expander II, 1969. Courtesy mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, on loan from the Artothek des Bundes.

In a more general sense, the anti-modernist attitude of many makers is remarkable in retrospect. On the one hand, they sometimes hark back to pre-modern rituals and archetypes, as in the early work of Hollein and Gunther Feuerstein. On the other hand, persuasive proposals for a new nomadism are conceived by Angela Hareiter.

Today’s posthumanism moves beyond merely criticizing modernity. After post-modernism, the whole humanist tradition, which can be summarised as the Enlightenment project, is now being questioned critically and in depth.

The connections that I make may seem tentative but I’m certain a (repeated) visit to the exhibition will reveal them to you as well. As is often the case it’s not so much the grand gestures; the megastructures or inflatables, that prove to be predictive of the future. It is the smaller, more subtle signals, in this case with regards to the human body, that manage to reverberate in the future. Which is to say; our present. Or is this perhaps the hammer in my hand talking? A tool by the way that you, the reader/visitor, are definitely not allowed take into the exhibition room.